March 06

March 06

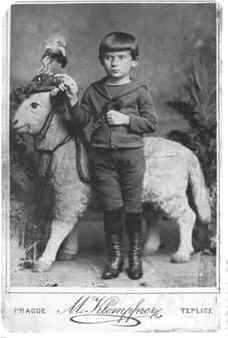

My Dear Son Franz

by Stephen E. Tabachnick

p. 2 of 2

You must admit, Franz, that despite your idealized claims that the Orthodox Jews of Poland and Russia are somehow more “genuine” than most of us Western Jews, you yourself are no more observant than I am, and possibly even less of a believer. As proof of your weak or nonexistent belief, I point to the Emperor in “The Great Wall of China,” whose intentions can never be understood, and who seems to symbolize your idea of God as a completely inscrutable being. And I have struggled through the story told by the priest in The Trial, concerning the man who is never allowed to enter the doorway made especially for him. As little as I pretend to understand these strange tales, it is obvious to me that they are somehow meant to represent your idea of man’s relationship (or non-relationship) with the Divine. You were an adult when you wrote this crazy stuff, not a petulant child going to synagogue against his will. Isn’t it much too easy for you to hold me responsible for your own lack of faith?

You have somehow dreamed up the idea of going to Palestine, and you attend Zionist meetings. Yet you must admit that in actual fact you can barely bring yourself to leave Prague. At most, you might travel to Berlin or to Vienna. So why keep criticizing me for not being a Zionist? I have no desire to start over in a new country now. It has been hard enough to establish myself here.

Granted, our lot here in Prague is a very dangerous one because of the hatred that surrounds us. However, unlike many Jews who wish to avoid that hatred by ascending the social ladder into European society and melting into the Christian crowd, I have never considered conversion. Neither I nor your mother has ever felt that we could betray our identity and make that compromise. Wasn’t it therefore wrong of you to portray us in “Metamorphosis” as a Christian family? Were you trying to say in that story that we are so assimilatory as to be like a Jewish family that had converted to Christianity? And that we therefore despise your substitute Gregor because he had “backslid” into an interest in Orthodox Judaism, including a change of dress and eating habits? Is that the meaning of Gregor’s being a bug? If so, Franz, here is yet another example of your perverse fictional hyperbole and obfuscation. I must remind you again that we have not converted and that you are certainly not Orthodox. And now you are after that Christian woman, Milena, who is married to one of your bohemian friends.

Which brings me to your most bitter accusation against me, your idea that I am somehow responsible for your failure to marry. Once again, I beg you to stop blaming me, and to start taking responsibility for your own life! Please realize, finally, that you are only using me as an excuse for your own failures. The truth is that whenever you introduced or mentioned your girlfriends, I felt sorry for them even when I did not like them very much. You deliberately choose women whom you won’t be able to marry, while keeping up the pretense that you are seriously interested in them. Whether it was Felice Bauer, who I could see was boring you during the five long years of your “courtship,” or Julie Wohryzek, who was certainly too uneducated for you, or now Milena, who may be up to your intellectual level but who is already married and a Christian, it all amounts to the same thing. You cannot handle the challenges of marriage and sustained commitment. You are simply too narcissistic, always concentrating on your own needs and feelings first. You have nothing left over to give anyone else, especially now that you are ill. Don’t think that it makes me happy to say this. Your mother and I both hoped for grandchildren from you, and now you are almost forty. But facts are facts. Instead of wanting to marry, all you care to do is to use your girlfriends to satisfy your sexual needs and to serve as recipients of the lengthy, no doubt convoluted letters that I have so often seen you writing. Although I have not read those letters, I will hazard a guess that they are most certainly not about the girls to whom you are writing, but only about yourself--perhaps the only person whom you will ever truly love.

Franz, because you have never been married (and have no illegitimate children that I know of), you do not know what it is to be a parent. This is why you can be so critical of your mother and myself, cataloguing every error and fault, real or alleged, that we supposedly committed while we were raising you. You are like a lawyer arguing a case (but remember please who financed your legal education!), or a skilled journalist penning a venomous editorial, but we are only ordinary people, untrained as lawyers and polemicists and so unable to defend ourselves well against such a skilled attack. Certainly we made mistakes while raising you children. All parents do; bringing up a  child is a constant learning process, and it takes time to comprehend each child’s special sensitivities. I realize that I, probably like all parents, was hypocritical when telling you not to drop food on the floor while dropping it myself, and when forbidding you to curse while occasionally using foul language myself. I apologize for that. But aren’t you now mature enough to realize that I had your good at heart when admonishing you about these things? Let me ask you this: What kind of person lives in his parents’ house when he is thirty-seven years old, and criticizes them endlessly while partaking of their largesse? You are simultaneously displaying the psychology of an adolescent and an adult. To the adolescent’s love of finding examples of his parents’ supposed hypocrisy, you add the mercilessly critical perspective of a mature person. You may never find the strength of character to build a life separate from your mother and myself, Franz, but please direct your energy toward that goal, rather than at us!

child is a constant learning process, and it takes time to comprehend each child’s special sensitivities. I realize that I, probably like all parents, was hypocritical when telling you not to drop food on the floor while dropping it myself, and when forbidding you to curse while occasionally using foul language myself. I apologize for that. But aren’t you now mature enough to realize that I had your good at heart when admonishing you about these things? Let me ask you this: What kind of person lives in his parents’ house when he is thirty-seven years old, and criticizes them endlessly while partaking of their largesse? You are simultaneously displaying the psychology of an adolescent and an adult. To the adolescent’s love of finding examples of his parents’ supposed hypocrisy, you add the mercilessly critical perspective of a mature person. You may never find the strength of character to build a life separate from your mother and myself, Franz, but please direct your energy toward that goal, rather than at us!

The part of your letter that I find most puzzling is why you have never come to me directly with your complaints. You live in our house; you eat our food; and you help in our factory. I have known that you are eccentric, but until now I thought that you were fairly happy on the whole (outside of your problems with women, your health problems, your complaints about work, and your bizarre stories). If you had simply told me about the concerns that most upset you, I might have been able to relieve them to some degree.

You may be surprised to hear me say this, but I am certain that you will indeed become a famous writer. Your letter, with all of its eccentricities and distortions, convinces me of that. You are like a reverberating instrument, inside of which every touch or disturbance bounces around for days, weeks or months instead of simply fading away. But this very sensitivity of yours, Franz, is yet another reason for you to forgive any perceived slights. You should realize that no parent could raise someone like you without being blamed for a whole world of things, real and imagined. Especially a parent like myself, who suffered great poverty and humiliation before achieving success in business. You are tired of listening to the story of my life, I know, but that story establishes one simple fact: You, Franz, have had the luxury of becoming a writer because I did whatever I had to do to rise from manual work in a little ghetto to the ownership of a respected shop, and to provide for my family. Do you think that it was easy for me to attain this position? An intellectual son with a professional education is not in a good moral position to criticize a hard-working father, especially when that father has paid for his son’s expensive tuition. And if, because of your fine education, you are more discerning of life’s nuances than I am, be grateful for that instead of blaming me for lacking your educational development!

This response is growing long, though it is still far shorter than your letter. Franz, please remember that I love you, and that I will unhesitatingly support you when you are in need, as I always have done. You may find it odd that instead of completely resenting your letter, I will now admit that I am to some degree grateful for it. It is the one piece of your writing that I can truly understand. Moreover, your letter makes clear what I have thought for some time: that without me to blame, you would have very little to write about. And since a wicked, dominating father makes a much more exciting subject than a generous, supportive one, in your writings you have simply invented such a wicked father, whether or not such a figure accords with reality. Maybe one day you will be mature and honest enough to admit that, at least to yourself.

Sincerely, your loving father,

Hermann Kafka

Stephen Tabachnick's nine books include, most recently, "Fiercer than Tigers: The Life and Works of Rex Warner" (Michigan State University Press, 2002), and "Lawrence of Arabia: An Encyclopedia" (Greenwood, 2004).