April 06

April 06

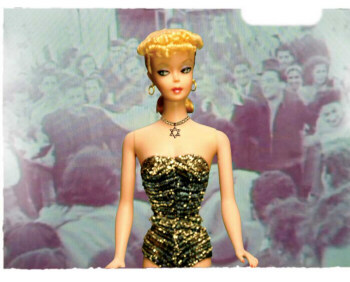

Tribal-Princess Barbie

Leah Koenig

Barbie: model, ballerina, doctor, fashionista, icon, astronaut, rockstar…Jew?

America’s favorite plastic shiksa might be able to explain how today’s generation of Jews feels about being Jewish. Barbie was created in 1959 by Ruth Handler (a Jewish woman). But Barbie did not particularly resemble Handler’s daughter Barbara, after whom the doll is named. With her blond-bombshell image and perfect nose, The Tribe suggests that Barbie symbolizes the goyishe ideal for a generation of Jews who assimilated their way to the American Dream. Bruised by a history of antisemitism and marginalization, and living in an age before cultural specificity was cool, these Jews chose to play down their tribal uniqueness and blend in to their surroundings. All-American Hollywood is one product of this generation; the Barbie doll is another.

But what about today’s generation of American Jews – those who grew up playing with Barbie in an environment that promoted tolerance, nurtured personal expression, and came to celebrate multiculturalism and ethnic diversity?

According to director/writer Tiffany Shlain’s short film, The Tribe (which she co-wrote with her husband Ken Goldberg), today’s American Jews are free to reclaim the Jewish identity that Handler’s generation stifled, and celebrate the cultural and even physical oddities a previous generation rejected (or surgically altered). AsThe Tribe’s narrator, Peter Coyote, puts it, today’s Jews are “pro choice – as in they choose to tell someone if they’re Jewish.”

The 18-minute film uses humor, experimental film techniques, and a broad-stroke approach at history to uncover the questions woven into the collective and individual identities of today’s American Jews. Many of the film’s scenes are diorama-style and use strategically-posed Barbie and Ken dolls to represent images of Jewish American life. (This technique was also used by director Todd Haynes in his 1987 movie, Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story.) The Tribe subtly nods to the role Barbie has played in fostering a sexist and sometimes dangerously unrealistic expectation of American beauty – although much less explicitly than Haynes’ film. Shlain explains that The Tribe is too short to fully explore this angle. (Besides, most pop culture-savvy Americans are already aware that a real woman with Barbie’s exaggeratedly fecund proportions would not be able to stand on two feet.)

The Tribe was recently featured at The Sundance Film Festival, awarded Director's Choice at the Black Maria Film Festival, and is scheduled to run at The Tribeca Film Festival throughout April. I spent some time on the phone with Ms. Shlain (braving the three-hour New York to Los Angeles time difference) discussing her film and the impact it is having – both within and outside of the tribe.

Z: Let’s start with a little bit about your background as a Jewish filmmaker. Is this the first time that Jewish questions have factored into your work?

TS: This is my first Jewish project. Looking back at my career in the context of being Jewish, I can say that I am always asking questions. So perhaps all of my work is Jewish. But this is my first Jewish theme. I always knew I would eventually do a project that dealt with my Jewish identity – I figured at some point it would be something I was ready to delve into.

Z: What's your favorite work you have done?

TS: This is my 8th film. I had film at Sundance a few years ago that I was really happy with and is going to be re-released for the upcoming election. It’s called Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness and is about the erosion of reproduction rights in our country. The style used in The Tribe and Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness is something I’ve been developing over many years. It’s experimental and uses a lot of humor as a way into complicated issues. My strategy is to use short films as a trigger for discussion and action. If you have a long film, it dominates the whole evening. But if you have a 15-minute film followed by provocative discussion, then the evening becomes more about the audience’s reaction and ideas. The film is almost like the appetizer and the discussion is the main course.

LK: I understand you have an online forum for discussion of The Tribe? What other approaches have you tried to get people talking about your film?

TS: Usually when a film comes out, people get excited about it but have to wait a year for the DVD to come out. While we were in production of the film, we concurrently made this whole discussion kit that went with the film. So when we had our premiere in San Francisco, the discussion kits were available…the whole concept [is for the kits to be] home-screening kits. It’s an amazing viral thing – and it’s been the real innovative component for people who might not otherwise go there with discussion.

LK: It seems that the central question The Tribe asks is, “what does it mean to be a part of any tribe, and specifically the Jewish tribe? How did this question first emerge for you as a compelling one to address in a film?

TS: I’ve always been fascinated when people say, “I’m a member of The Tribe” – it gives me this flash of pride, like I’m part of something. It’s a really interesting thing because I’ve always felt like an outsider and I think perennially Jews have always felt like outsiders. Also, my husband and I just thought the phrase “Member of The Tribe” was such an interesting one to deconstruct – it’s so rich and dense. What is a tribe, and what is membership, and what does it mean today in the 21st century when we no longer live in shtetls and we’re intermarried. . . . I think for our parents’ generation, the goal was assimilation and looking like all the other tribes. Our generation is much more able to reclaim our tribe – multiculturalism is so much more a part of our world. Our generation can mix cultures like a dj mixes sounds. We can take various things from different cultures that we’re interested in and blend them together.

L: Yes, but at what point does a tribe become so internally diverse and hybridized that it loses the right to become a tribe?

T: That’s a great question – yes there are a lot of hybrids. But I think there’s something ineffable at the core of being Jewish. There are so many people in our parents’ generation who are afraid that we’re losing our tie to tradition – but listen, we’ve been around for so many thousands of years with worse things happening than assimilation. And somehow we’ve managed to continue the rituals and traditions and to reinterpret them. One line at the end of the film says, “Each generation asks old questions in new ways.” I don’t think [The Tribe] uncovers completely new questions, but we want the film to intrigue people enough to delve into their own history. Personally, I knew a lot about other people’s history, but not my own Jewish history. Working on this film was a real eye-opener for me.