May 06

May 06

France’s Jewish Prophets: Alain Finkielkraut, Albert Memmi, and the Looming Crisis of Liberalism

by Dr. Michael Shurkin

p. 2 of 3

In an interview published in June 2004 in L’Express magazine, Memmi expressed skepticism that such a “Reformation” is even possible. “The link between religion and society” is too anchored in Arab mentalities and the Arab consciousness, and in "a philosophy in which the religious and the profane coincide, which is contrary to the exercise of a critical spirit. Without a critical spirit, you cannot have before nature the liberty of thinking that is indispensable for mastering it. For criticism is forbidden in most Arab countries, under pain of prison or exile." (Albert Memmi, “Les Arabes ne peuvent qu’accepter les valuers de l’Occident,” L’Express, June 14, 2004.)

Critically, Memmi does not spare the former colonized who have settled in France, nor their children, who concern him the most:

The son of the immigrant is a sort of zombi, without deep attachment to the soil on which he was born. He is a French citizen, but he does not exactly feel French; he only partially shares the culture of the majority of his fellow citizens, and not at all the religion. But neither is he an Arab…truly he is from another planet: the suburb.

Memmi, Portrait, p. 141

Memmi’s suburb roughly approximates the American inner city, a place where the police seldom tread and where “youths” (Memmi notes the French preference for that vague term rather than anything that might specify which kind of youths) fabricate their own identities around delinquency and the adaptation of American hip-hop culture. Graffiti, rap, and vandalism, particularly the burning of cars: these are the aesthetic gestures of “protest and provocation” of the sons of France’s decolonized immigrants. Finally and perhaps despairingly, Memmi has lately questioned whether or not France can ever acculturate its new minorities, both because of the resistance within the Muslim community, and reluctance within the larger French one.

Finkielkraut Agonistes

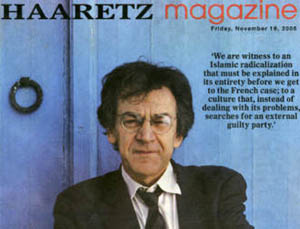

It is here where Alain Finkielkraut takes up the baton, although in an altogether different context. On November 18, 2005, the Israeli newspaper Haaretz published an interview with Finkielkraut about the riots that were then setting the immigrant suburbs of Paris and other cities ablaze. (A translation appeared here. Finkielkraut’s stance paralleled Memmi’s -- critiquing the state of France’s “Arabo-Muslim” minorities in the name of  Enlightenment and French Republican values -- but unlike Memmi, Finkielkraut lost editorial control (and perhaps control of his tongue), and various media, beginning with Haaretz itself, repeatedly repacked his views to as to make them all the more newsworthy.

Enlightenment and French Republican values -- but unlike Memmi, Finkielkraut lost editorial control (and perhaps control of his tongue), and various media, beginning with Haaretz itself, repeatedly repacked his views to as to make them all the more newsworthy.

In the Haaretz interview, which presented Finkielkraut as a “deviant, even very deviant voice,” Finkielkraut denounced the tendency of the makers of French public opinion to find excuses for the violence by blaming it as the natural response to French racism and the social conditions of the rioters. “In France,” he said,

they would like very much to reduce these riots to their social dimension, to see them as a revolt of youths from the suburbs against their situation, against the discrimination they suffer from, against unemployment." But Finkielkraut placed the blame on the rioters themselves, and thought it no accident that the rioters were the descendents of black African and North African immigrants, nearly all of them Muslims:

The problem is that most of these youths are blacks or Arabs, with a Muslim identity. Look, in France there are also other immigrants whose situation is difficult—Chinese, Vietnamese, Portuguese – and they’re not taking part in the riots. Therefore, it is clear that this is a revolt with an ethno-religious character…Is this the response of the Arabs and blacks to the racism of which they are victims? I don’t believe so, because this violence had very troubling precursors, which cannot be reduced to an unalloyed reaction to French racism.

Finkielkraut contrasted the rioters' actions with that of his own family, this time with reference to the Holocaust:

My father was deported from France [to Auschwitz]…This country deserves our hatred: What it did to my parents was much more violent that what it did to Africans. What did it do to Africans? It did only good. It put my father in hell for five years. And I was never brought up to hate. And today, this hatred that the blacks have is even greater than that of the Arabs.

Noting that Arab youths booed the national anthem and the French flag at a football match between France’s famously multi-racial national team and Algeria’s, Finkielkraut asserted that he saw

[the] very declarations of hatred for France. All of this hatred and violence is now coming out in the riots. To see them as a response to French racism is to be blind to a broader hatred: the hatred for the West, which is deemed guilty of all crimes.

Finally, particularly incensed that the rioters’ favorite target was the school, an institution he had long lauded as the Republic’s pre-eminent tool for emancipation, Finkielkraut concluded that the riots were tantamount to an “anti-Republican pogrom.” He said that the rioters hated the Republic not because of any past colonial sins, but because the Republic, retrospectively and according to the resentment nourished by the Muslim minorities, was a stand-in for the abstract “victimizer” to blame  for the “victim’s” ills. Finkielkraut saw in the riots the failure of the “multicultural” model, and feared that the perceived failure would lead the French public to conclude precisely the wrong thing: that schools had to become “nicer.” In fact, well-intentioned French intellectuals and public officials, he complained, were partially to blame, for exaggerating of France’s history of colonialism and slavery and fostering an identity of victimhood and resentment -- and while attacking the memory of the Holocaust.

for the “victim’s” ills. Finkielkraut saw in the riots the failure of the “multicultural” model, and feared that the perceived failure would lead the French public to conclude precisely the wrong thing: that schools had to become “nicer.” In fact, well-intentioned French intellectuals and public officials, he complained, were partially to blame, for exaggerating of France’s history of colonialism and slavery and fostering an identity of victimhood and resentment -- and while attacking the memory of the Holocaust.

The Haaretz interview touched off a scandal. Portions immediately began circulating in French, and on November 23, the leftist French anti-racism organization Movement Against Racism and for Friendship Among Peoples (MRAP) filed a suit against Finkielkraut for inciting racial hatred. On November 24 Le Monde’s editor, Sylvain Cypel, smelled blood. He lifted the most provocative lines from Haaretz and published them out of context in the guise of an interview synopsis under the headline “The ‘Very Deviant’ Voice’ of Alain Finkielkraut in the Daily Haaretz.”

Finkielkraut tried to stem the damage. He appeared on the Europe 1 radio network seeking to apologize and explain his words. Among other things, Finkielkraut disavowed the interview's more extreme language, and attacked its redaction in Le Monde:

From the puzzle of quotations in Le Monde, there emerges an odious person, unlikable, twisted, whose hand I would not want to shake. They tell me – and here the nightmare begins – that that person is me, I am being told that I inhabit that fictional body, and that I must answer for it before the court of public opinion. So I want to defend myself…

The next day, Le Monde printed his rather ambivalent statements (“I apologize to those whom the person who I am not has hurt…the lesson is that I must no longer give interviews with newspapers that I don’t control or the fate or translation of which I cannot control”). MRAP accepted Finkielkraut’s apology and renounced its plans to sue him even though its leader, Mouloud Aounit, “doubted the sincerity of Mr. Finkielkraut’s excuses.”

But the polemics had only just begun. Minister of the Interior Nicolas Sarkozy, who had notoriously referred to the rioters as “rabble,” endorsed Finkielkraut as an “intellectual who brought honor to French intelligence,” noting that “if so many people critize himI it is because what he says is right.” Indeed, according to Sarkozy, it was not Finkielkraut and his fellow conservatives but the liberal consensus that were to blame for the National Front’s recent electoral successes. Sarkozy added,

This is the only result of all those well-intentioned thinkers who live in a salon between the Café de Flore and the Boulevard St. Germain, and who are surprised that France resembles them so little.

Naturally, such an endorsement didn't help Finkielkraut -- labeled by one editorialist "the Sarkozy of the intellectual world" -- and his reputation within that influential clique.

Lower: Jean Benabou, The Conversation