June 06

June 06

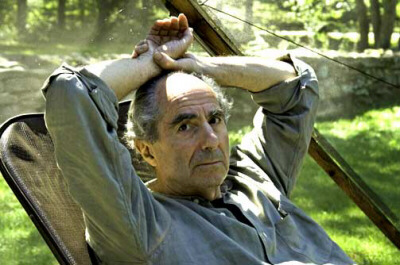

Live By No Man's Code: The Religious Forms of Philip Roth's "Everyman"

by Stephen Hazan Arnoff

p. 2 of 3

Roth notes that the working title for Everymanhad been The Medical History. In Everyman's journey, the body in all of its clinical detail – without divine force or intervention to animate it – travels alone. Yet if a body lacks the traditional religious tension of a companion soul charged with navigating its return to the ethereal realm, how, according to Roth, is the body meant to spend its time and define its meaning on earth?

In an interview posted by The Guardian on December 14, 2005, Danish journalist Martin Krasnik asked Philip Roth if he was religious. "I'm exactly the opposite of religious," he said. "I'm anti-religious. I find religious people hideous. I hate the religious lies. It's all a big lie." Then Roth offered the interviewer a question of his own: "Are you

religious yourself?" "No," said Krasnik, "but I'm sure that life would be easier if I was." "Oh," Roth answered, "I don't think so. I have such a huge dislike. It's not a neurotic thing, but the miserable record of religion. I don't even want to talk about it. It's not interesting to talk about the sheep referred to as believers. When I write, I'm alone. It's filled with fear and loneliness and anxiety – and I never needed religion to save me."

religious yourself?" "No," said Krasnik, "but I'm sure that life would be easier if I was." "Oh," Roth answered, "I don't think so. I have such a huge dislike. It's not a neurotic thing, but the miserable record of religion. I don't even want to talk about it. It's not interesting to talk about the sheep referred to as believers. When I write, I'm alone. It's filled with fear and loneliness and anxiety – and I never needed religion to save me."

For the hero of Everyman, a number of options emerge for handling "fear and loneliness and anxiety" after retirement from life as a company man gives his already ubiquitous thoughts of mortality a chance to echo more loudly than ever before. Family offers him one possible direction of making meaning – despite a trail of divorce behind him – most particularly in the form of his beloved daughter Nancy and her twins in New York City. But after 9/11, he moves away from Manhattan out of fear of more terror attacks, settling in a plush retirement community on the Jersey Shore. Once ensconced there, he quickly finds himself bored by opportunities for social succor with fellow old folks and too ambivalent about engaging in the faded draw of sexual pursuits. The hero, always dreaming of life as an artist while perched for a worker's lifetime at a desk in the office, takes up painting intensely for a period of time. Eventually, even this passion drains and loses its appeal.

The hero of Everyman's lack of meaning and "soullessness" is reminiscent of the modern conundrum described by German sociologist Max Weber a century ago. According to Weber, societies founded upon covenants of salvation eventually lose touch with their original charismatic, prophetic impulse. Think of the "National Anthem" recited by children every day at school, "In God We Trust" rustling in your wallet, or Emma Lazarus' "Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free" engraved on the Statue of Liberty. For any one paying attention to the recent history of the United States, these salvational anthems and creeds are primarily devoid of meaning in real time. The words and sentiments are hollow, rationalized, and unrelated to the day-to-day life of the vast number of Americans. Devoid of animate meaning, religious roots give way to static social structures and self-serving authority which Weber termed the "iron cage."

Everyman's hero's deeds are not granted a moral or immoral value as in the case of the Christian allegory. He lives without a personal or communal charismatic, soulful force to guide him through the "fear and loneliness and anxiety" around him. Philip Roth, taking the artist's path of discovery and meaning, has his devotion to writing to guide him through emptiness, but Roth's hero goes "from being, entering nowhere without even knowing it." His death is described as akin to entering the endless, idyllic ocean of the Jersey Shore in which he had frolicked in ecstasy as a boy. Roth's description of the Great Beyond as the ocean is an absolute contrast to the loneliness and pain of his hero dying without an anchor – despite his marveling at the memories of life's wonders as he slips away. The ocean represents a cluster of essential religious, mythic symbols: the divine retribution of the Flood, the infinite realm of subconciousness knowledge or wisdom, the cosmic river that girds the universe, the source of all life, or the boundaries of the earth from which humans may not pass. The sea is a mirrored manifestation of the endless possibility of heaven on earth, while life without meaning falls flat with the thud of iron in the mud. Standing over his casket, Everyman's daughter Nancy quotes her father's resigned, secular code for living within the "iron cage" of a rationalized, spiritless world:

There's no remaking reality…Just take it as it comes. Hold your ground and take it as it comes. There's no other way.

Roth and the Rabbi

The Guardian's Krasnik asked Roth to reflect on the Jewishness of his work in their interview as well:

It's not a question that interests me. I know exactly what it means to be Jewish, and it's really not interesting. I'm an American. You can't talk about this without walking straight out into horrible clichés that say nothing about human beings. America is first and foremost ... it's my language. And identity labels have nothing to do with how anyone actually experiences life.

Many make claims for the appropriateness of advocating either for or against Roth's "Jewish identity." On the face of it, he is a writer who has devoted much of a sterling literary career to work that is primarily about Jews. Does this not a Jewish writer make? Yet the matter is complicated. A clear trick of Roth's most recent writing has been to turn nominally Jewish figures – Nathan Zuckerman, Swede Levov, Coleman Silk, and Everyman's nameless hero – into distinctly American models for dissecting the crash and burn of particularly American kinds of mortality. The Jew quite literally becomes an American "everyman" in Roth's milieu. Yet in the area of explicit Jewish content, Roth has also created The Plot Against the Jews, a nightmare of American and world history in which Jewish continuity, always said to hang by a thin thread, is  clipped by the Nazis even in America. Without entering explicitly into the types of political agendas and "horrible clichés" about Roth the Jewish writer that raise his ire, it is useful to think about Philip Roth generally – and specifically in context of Everyman– as a purveyor of contemporary American religious fables containing useful projections into all religious realms, Jewish ones (obviously if not essentially) included.

clipped by the Nazis even in America. Without entering explicitly into the types of political agendas and "horrible clichés" about Roth the Jewish writer that raise his ire, it is useful to think about Philip Roth generally – and specifically in context of Everyman– as a purveyor of contemporary American religious fables containing useful projections into all religious realms, Jewish ones (obviously if not essentially) included.

Artists make us of religious content continually regardless of their respect or antipathy for religion itself because religious content is so rich with ideas and inspiration. It is not necessary to drive Roth the writer or Roth the private person into a Jewish or religious corner in order to understand the contemporary religious use for his iconoclasm. Roth's vision comes to light when comparing his reworking of the Christian drama "Everyman" with a fable from the Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Avodah Zarah 17a, probably recorded in its current form in the 7th or 8th century. The story likely circulated in various forms for centuries in the realms of the Mediterranean and Near East where Judaism, Islam, and Christianity first took shape:

They said of Eleazar ben Durdia that there was not a prostitute in the world with whom he had not had sex at least once.He heard that there was a prostitute in a town by the sea who took a full purse of dinars as her fee. He took a purse full of dinars and came to her, crossing seven rivers to get there. At the moment of truth she farted. She said, 'Just like this fart will never return to its place, so too will Eleazar ben Durdia not be received when he turns in repentance.'

He went and sat between two mountains and hills. He said, 'Mountains and hills, ask for mercy upon me!' They said, 'Before we can ask for mercy upon you we must ask for mercy upon ourselves, as is says, For the mountains shall depart and the hills be removed …' (Isaiah 54:10). He said, 'Heavens and earth, ask for mercy upon me!' They said, 'Before we can ask for mercy upon you we must ask for mercy upon ourselves, as is says, For the heavens will disappear like smoke and the earth will wear out like cloth...' (Isaiah 51:6). He said, 'Sun and moon, ask for mercy upon me!' They said, 'Before we can ask for mercy upon you we must ask for mercy upon ourselves, as is says, The moon will be humiliated and the sun will be shamed...' (Isaiah 24:23). He said, 'Stars and constellations, ask for mercy upon me!' They said, 'Before we ask for mercy upon you we have to ask for mercy upon ourselves, as is says, All of the heavenly host will melt...' (Isaiah 34:4).

He said, 'It depends on me and me alone.' He put his head between his knees and shook with weeping until his soul departed. A heavenly voice declared, 'Rabbi Eleazar ben Durdia is ready for the World-to-Come!'

In both Everymanthe novel and the story of Eleazar ben Durdia a hero battles both moral codes and his own mortality. Wise visitors offer direction urging the hero towards death in each fable. In the talmudic story, natural forces personified as rabbinic teachers quote biblical verses, citing their obedience and even lack of choice before God. Their role is to turn Eleazar ben Durdia towards himself so that he might recognize that only he can save himself through body-emptying weeping, a well known mystical practice which seems not only to demonstrate his worthiness for the next world, but essentially melts and merges his physical body into the matterless world beyond. Roth's Everyman, in the moments before departure from the world and perhaps as a literary nod to the Good Deeds (but not repentance!) of the play, says, "[H]e had only to yearn for them to conjure them up." These are the figures of the family love of his boyhood, carriers of the innocent moments of his past that are the closest thing to Good Deeds he can find.