August 06

August 06

Spirituality in a Time of Seriousness: Levels and Religion

by Jay Michaelson

p. 2 of 2

The problem is that the levels of truth in religion and spirituality are mixed up all the time, not least by religionists, and atheists, themselves. Not mixed up in the sense of incoherence -- rather, mixed up in the sense of disagreement and controversy.

First, consider the "normal," unreconstructed religionist. For such a person, religion really is about the cliche of following rules, doing what you're supposed to do, and believing in the literal truth of the stories of the Bible. Religion is, in this light, still conceived of as about the "higher" human faculties -- but not anything trans-rational, personally spiritual, or contemplative, only moral, intellectual/theological, and ethical. Religion, in this mindset (which is far more common than my own, of course), exists on the level of everyday reality, and is about a set of beliefs, precepts and principles, to which the individual will is to be conformed. We may still have religious experiences, of course -- as I've written about before, both Bushian evangelism and Al Qaeda Islamism deeply value personal religious experience -- but only within the bounds of religion, and, crucially, only interpreted within fixed categories. Anything more than that is "putting yourself above the Bible" or straying from the true path.

This is what Wilber calls "interpreting a state in light of your stage" -- some kind of mind-state, which a meditator might just see as a mind-state, or a contemplative experience, is interpreted in mythic language, e.g., as a message from the Virgin Mary, or Allah, or Christ. And the truth to which that experience refers is neither psychological-subjective nor Absolute -- but relative, normal, and everyday. So: Jesus told me that I was going to win the football game. Or: The Archon El told me that the world will end in 2012. Contemplative mindstates, interpreted down in terms of everyday reality.

(As an aside, perhaps this is one reason American Jews are more progressive in their religiosity than Israelis: they literally don't understand the words they are singing. Even when they do, the literalism of myth is still distanced by the language and thus not "ridiculous." Statistically, only about 15% of American Jews say they believe the statements of the Bible and liturgy. The rest of us find it easier to just sing.)

Second, consider the secular fundamentalist -- less familiar, and less dangerous, but it is still the exact mirror image of its religious twin. Just as the religionist does, the secular fundamentalist, believes that religion is about true or false historical statements, and obedience to various pre-set principles of belief and action. Only she doesn't believe any of them. And, also just like the religious fundamentalist, she denies the validity of trans-rational religious experience, in her case lumping it together with pre-rational nonsense. Crystal healing is bunk, and therefore so is all "energy" work. Made-up images of angels are delusion, and therefore so is any insight gained through meditation.

Granted, the secular fundamentalist gets plenty of help from the New Age, which confuses pre-rational and trans-rational all the time. But the great irony is that the skeptic thinks he is the voice of reason and clarity, whereas he in fact is the voice of fear and ignorance -- because he simply does not know what he is talking about. Not because the "trans-rational" faculties are beyond human capacity, but because he simply hasn't tried to experience them. Simply go on retreat for seven days, and you'll see that you can have deep insights into your own consciousness while at the same time perfectly maintaining the rational faculties of doubt, inquiry, and the rest -- and while, of course, also tending to all the "lower" needs of your body. Or, simply do a "magic" religious ritual, and you'll see that, whatever the source of the mindstate, mindstates and shifts and insights do indeed occur.

Of course, none of this says anything about the mythic structures in which religious experience is interpreted -- that's on a "lower" stage than the experience itself. Obviously, the move from a mystical experience to "I had an experience of Jesus Christ" is an interpretive one, which is susceptible to questioning. But the experience itself, purely as an experience, is not. As the bumper-sticker says, dancers also looks insane to people who can't hear the music.

Third and finally, consider the New Age enthusiast. He, too, has a contemplative experience, but ascribes to it all sorts of relative-world power. Such as: If everyone meditates, there will be world peace. Or: if Olmert and Nasrallah would just look inside themselves, they would discover their inner wisdom and war wouldn't happen anymore. Nonsense. The experience is the experience. It has transformative personal power. It may, indeed, prevent violence in the long-term, as people slowly learn to cultivate more compassion and less ugliness. But in the short term, all the conventional rules of engagement still apply.

In fact, to separate out the "higher" moment of religious/contemplative insight from the "lower" mythic language in which it has been laminated is, itself, a luxury reserved for the small percentage of people privileged and interested enough to do it. This is the insight and the failing of Jewish Reconstructionism, which gets the theology more "right" than any other denomination, but which errs in thinking that theology is really important. As Wilber acknowledges, most people have more pressing concerns: emotional comfort when a loved one dies, or pure physical survival. Insisting on proper god-language when someone is in the hospital would be the problem of the Kansas Cake all over again. When a fundamental need is unmet, the higher questions look like doodles.

So, in all three cases -- the religionist, the secularist, and the New Age enthusiast -- it's all the same problem: mistaking levels of religion, or reality, leading to great mistakes about the value and role of religious/spiritual experience. On the one hand, spirituality in a time of seriousness can look like decadent. On the other hand, if we never ask the higher questions, we remain trapped in the flatland worlds of secular and religious fundamentalism. It's not that life can't be happily lived in that way: life can also be happily lived without fine wine, music, or the Super Bowl. But for some people, it will be impoverished. Both higher and lower are important, but they each have their different takes on "truth," and talk past each other when they argue about what's essential and what is not.

4. Religion Reconstructed and Un-

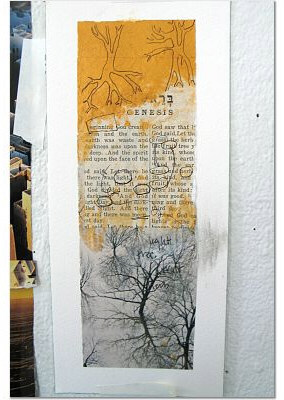

This is also why it's so hard for a contemplative to translate her theology into a shared religious vocabulary. To take a Jewish example, consider the question of the divinity of the Torah. In traditional categories, either God wrote the Torah, in which case we better listen to it (religionist), or people made it up, in which case we don't really need to (secularist). But I, like the Reconstructionists, end up somewhere less clear and more complex. I don't necessarily believe in what the Good Book says, but I do believe in something which inspired it. And the less attached I am to the idea of literal Biblical truth, the more my appreciation of the Bible grows, because then I can see it not as bad science or bigoted law, but as a beautiful effort to address real concerns about identity, survival, distinctiveness, and control. And then I can translate the Bible's concerns to my own, since I share so many of them.

Unlike the New Age enthusiast, I don't think that the "Something which inspired" the Bible is experienced the same way by me and by men in the 6th century B.C.E. Unfortunately, I don't think my Biblical forbears had an idea of a "transparent God" of whom it is said "God does not exist; God is existence itself." No, I think they had a notion of a human-like deity in the sky who presides over the world he has created, and who cherishes his special people. But I do think that that belief answered questions that are similar to ones I have, and with wisdom that accumulated over centuries of community, folklore, and story. And because I was raised in this civilization, its tools and even its myths feel natural to me. I may not believe in its statements about God, but what statements about God make sense anyway?

That is, of course, a rather complicated -- and yet still quite partial -- answer. It fails badly as a creed for large numbers of people, most of whom lack either the time, the interest, or the aptitude for parsing all these theological arguments. It also puts a large gulf between me and those Jews who really buy into the Jewish myths in a literal, unreconstructed way. And it even fails the many people (including many 'traditional' Israelis) who would prefer to be "bad" traditional Jews rather than twist Jewish theology around to suit their view of the world. To me, it's honest theology; but to them, it's twisting. Fine, you don't believe the earth is only 5,766 years old -- don't believe it. But don't call yourself religious.

Here again, flatland fundamentalism: a notion that religion is about certain statements of fact that you either believe or don't believe. The same problem once again.

Whereas, in fact, the whole point of "there are no atheists in foxholes" is that facts, theologies, and dogmas are really not what religion is about at all. It's just not about that level of thinking -- it's about the deeper needs for a god, the primal yearning for a father or mother, and the desire for order in the midst of chaos.

This is how I maintain my religious lifestyle even absent a belief in Torah MiSinai, or the various permutations on that theme one can learn at progressive institutions, or any familiar theological apparatus at all. The apparatus doesn't dictate the practice; belief does not dictate love. The apparatus is both too low and too high -- too rational for the contemplative experience to which it attempts to relate, and too rational for the emotional needs that underlie its sophisticated rationale.

This is also how the most anti-spiritual religious Jews are, in a way, the most spiritual. These are the people who want no explanation provided for what they do, who insist that they are following God's word. In other words: their spiritual-emotional need to "follow God's word" is so strong that it can scarcely be seen at all.

And this is how secularism is itself a form of devotion. About a year ago, I mentioned the "there are no atheists in foxholes" adage in an earlier article. Zeek received an email from an irate reader who said that, while he had never been in a foxhole, he resented the implication that his atheism would be so easily compromised. I thought to myself: how many religious people have such strong and unwavering faith? And what deep needs -- for truth, for honesty -- underlie it?

A spirituality that cannot withstand the foxhole -- that does not deeply address meaningful human needs -- isn't worthy of the name. Because the ultimate lesson of "levels in religion" is that religion ought to speak on all of these levels: the highest level of the contemplative, the conventional level of the worker or the soldier, and the primal level of the human being in stress or pain. These levels do not speak well to one another, but a religious community is one which shares the vocabulary anyway. That way, there is a God to turn to when all is uncertain, a God to love when all is perfect, and a God to guide the times of in-between.

Who's to say which matters more -- the lower, fundamental needs, or the higher, heavenly hopes? Or the everyday world of families, communities, and love? And who's to quibble over the theological or atheological details? Whether it's God or atheism one clings to, it is the clinging (devekut) which matters: the "one fortunate attachment" in Buddhist terms, the "sharp dart of longing love" in Christian ones. Perhaps all the rest is commentary.

Jay Michaelson is currently chief editor of Zeek. He is teaching at Elat Chayyim, Easton Mountain, and Burning Man this month.