November 06

November 06

Funny Antisemitism is Good for the Jews

by Dan Friedman

p. 2 of 3

These libels have included specious interpretations of religious difference (e.g. that Jews use Christian blood to make matzah, a claim which scholar Gavin Langmuir notes is closely related, historically and philosophically, to the doctrine of transubstantiation), racial difference (Jews have big noses – a representation of the accuser’s sexual inadequacy, according to Sander Gilman), professional differences (Jews are financiers and financial cheapskates – because the Christian prohibition on usury and the Jewish continental network meant that they were needed and expert at transacting loans and payments at a continental level). Sometimes a piece of expert scapegoating just spreads. For example, water sources were so crucial and so precarious that, like thanking a Deity for a good spring, it made sense to blame the Jews for having a poisoned well.

In general, antisemitic Europeans blamed the Jews for anything they didn’t like. For religious antisemites the Jews were representatives of either Judas or Satan; for racial antisemites the Jews were ugly and in-bred; for cultural and paranoid antisemites the Jews were, in turn, the inventors and proponents of capitalism and Bolshevism. Even now, reactionaries parrot the tedious mid-twentieth century charge of Jewish moral relativism and yearn for a mythic time when Aryan mothers were sheltered by a blue sky and fed their babies on the milk of right and wrong.

The “New” Antisemitism

The “new” antisemitism, so much in vogue today, actually dates from the mid 1940s when the Shoah (a term against which Bauer also takes issue) and the establishment of the Jewish state in Israel gave the world two new Jewish-historical events to note. Really though, since Jewish victimhood was not essentially new (although the extent, the mechanization, and the national context were new and extreme) the change came from Israel showing it was a strong presence in the Middle-East – essentially since the end of the 1967 Six Day War. Once the Jewish state had showed it was secure on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean, it provoked certain Muslims who believed that the land should belong to Islam (although they seemed to feel less resentment for Coptic Christians, for example). Also, in addition to this nascent Islamist antisemitism and the reliable bigotry of the far-right, the left-wing became a haven for a certain type of antisemitism that shelters below the wing of anti-Zionism.

This has led some commentators to label this a “new” antisemitism, but the newness is arguably nothing more than contemporary forms of the same old antisemitism blended in with some Quranic strains of prejudice that were formerly obscured by European predominance. Perhaps Islam has taken over the mantle of endemic antisemitism once the preserve of Christianity. Or perhaps the target of global political vilification is the small but surprisingly strong Jewish state rather than the target of national political vilification being a small but surprisingly strong Jewish community. Perhaps the Nazi’s state-based and groundbreaking propaganda gave new fuel and inspiration to age-old prejudices, but the reasons and the general form is still the same.

Zionism is the promotion of Jewish self-determination in the land of Israel – however that land is defined. This means that there are clear theoretical distinctions between being an anti-Zionist (arguing that the Jews do not have a right to self-determination), not being a Zionist (not promoting the right of the Jewish state to exist), and being opposed to the policies of the Israeli government (arguing against Ariel Sharon or Ehud Olmert in the same way one might argue against Bill Clinton, George Bush, or Tony Blair). There is likewise a clear theoretical distinction between legitimate anti-Zionism (a particular legal-historical perspective about collective rights) and antisemitism (prejudice against Jews). In theoretical and legal discussions, and by thoughtful people in the academy, these niceties are observed, likewise in the discussions of committed and engaged Jews for whom the distinction is personal and crucial (“I am a Jew, I am not a Zionist”). But the sad fact is that many (if not most) anti-Zionists are either unaware of the antisemitic cultural prejudices they are recycling, or are using anti-Zionism deliberately as a respectable cover for their antisemitism.

Comedy and Civil Society

The genius of the documentary The Aristocrats was that it succeeded in being both insightful and amusing. Usually there’s nothing as earnest as comedians talking about their comedy. Conversations about timing, sequence, and the exact length that will maximize laughs from a moulded plastic dildo are no funnier than similar conversations about investments in the futures markets. The product is different, but the deadly seriousness of the endeavour is not to be doubted. Yet however serious the work may be, like the futures market, comedy is deeply unpredictable and depends on social events, at the same time that antisemitism is an illogical and historically pervasive phenomenon. Comedy can never directly refute or destroy antisemitism. Instead, comedy can both ridicule it and educate about it in equal measures.

But this comedic aspect of Horace’s “delight and instruct” is part of a larger social picture. In a multi-cultural society the difficulty lies in mediating shared space so that different cultures can talk to each other about the things that matter to us all. Comedy takes our assumptions and sends them up, letting us have, if we want them, a place of tentative discussion with and about other groups. Since active antisemitism is an irrational “passion” and passive antisemitism comes from lack of knowledge of information, comedy is the ideal medium both to educate the accidental antisemite and viscerally (rather than logically) to undercut the deliberate one.

In following this line of thought, what is said in jest about antisemitism defines what is said in earnest. Although not a simple correspondence, the struggle to delineate the boundaries of acceptable speech is increasingly carried out in the arena of comedy. As Jews we laugh at ourselves and we laugh at the ridiculous prejudices that others have about us. However, without a degree of power over the arena, this comic performance comes across as a form of minstrelsy (making fun of one’s own oppressed group for the benefit of the oppressing group), or, if it is performed by another group, of downright prejudice. There is a similar debate going on about Dave Chappelle and his characters in the African American community: Is it acceptable to laugh at ourselves in front of others, possibly even exclusively for the benefit of those others? This was the professed claim in the case of the Danish cartoons – that a disrespectful comic performance by outsiders had taken place in a forum in which the Islamic world felt totally disempowered.

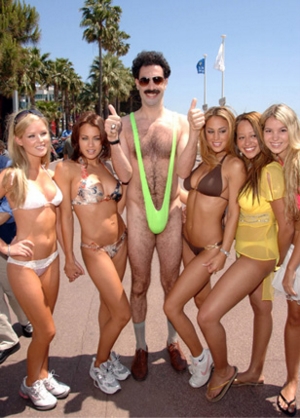

In discussing how comedy changes the way antisemitism is perceived, we are limited by the vocabulary available to us for talking about comedy. The laughter elicited for a joke about controlling Jewish mothers in The Hebrew Hammer is entirely different from the laugh inspired by Larry David eating the cookie of the baby Jesus. Different still is the laugh at Woody Allen thinking of himself perceived as a Hasidic Jew at the Hall’s dinner table. Different again is the Pamplona-esque “Running of the Jew” in Borat: Cultural Learnings… In our own self-observation we are obsessed with circumcision –from History of the World Part I to Sacha Baron Cohen’s “Shvitzin’” to the Late Night Players description of Matisyahu as “Hip-Hop from the Tip-Chopped.” It is hardly the worst stereotype to promulgate, but do we really want to reinforce the stereotypes of Jews as money-grubbing, mother-pecked, circumcised neurotics?

The danger of comedy is that it can reinforce stereotypes and trivialize hatred as well as belittling it, allowing the critique of the haters that “they are a joke,” but allowing them the excuse that “we were only joking.” The ease with which a group of people were encouraged to sing along with the abhorrently racist “Throw the Jew Down the Well” draws attention to antisemitism and its abhorrence, but it can also end up simply normalizing it. Clearly, the scapegoating of an almost invisible minority for the murder of the son of God is a pretty serious matter, and one which most churches have moved beyond. The parodying of the libel in Curb your Enthusiasm makes it difficult to take seriously at all.

Context is the Lens

Context is vital for understanding both antisemitism and the comedy that comes from it. Context provides the lens through which we see the performance – who makes it, to whom, and in what tone. The signs at airports mandating “no jokes beyond this point” are some of the latest reminders of how there is no longer any place for the slipperiness of humour when security is at stake. The context of antisemitism is likewise totally context-specific. For example, when the manager of an Italian restaurant in London seated us and went to fetch some sparkling water with the words “Ah yes, Jewish champagne,” it seemed like an antisemitic comment about being cheap. This was because he was not apparently Jewish and had no way of knowing whether we were Jewish or not. However, when a colleague – 8 years later, unprompted, and unaware of our previous experience – came out with exactly the same words upon being offered seltzer at our apartment in New York, that was, paradoxically, not antisemitism.