January 07

January 07

Start Making Sense: The "Elaborate Nonsense" of Poles, Jews, and the Holocaust

Mordecai Drache

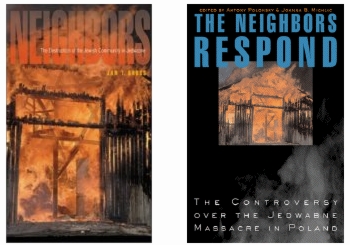

In late May 2000, a slim Polish edition of a work originally published by Princeton University Press – which by all accounts should have remained obscure – was reviewed in the major Polish daily Rzeczpospolita. Its title was simply Neighbors. Written by Polish-Jewish historian and sociologist Jan T. Gross of Princeton, the book's central thesis – supported in brutal, gut-wrenching detail – was that the murder of Jews in a Northeastern town in Poland called Jedwabne in July 1941 was conducted by Poles, not by the occupying Germans who had instigated it.

In late May 2000, a slim Polish edition of a work originally published by Princeton University Press – which by all accounts should have remained obscure – was reviewed in the major Polish daily Rzeczpospolita. Its title was simply Neighbors. Written by Polish-Jewish historian and sociologist Jan T. Gross of Princeton, the book's central thesis – supported in brutal, gut-wrenching detail – was that the murder of Jews in a Northeastern town in Poland called Jedwabne in July 1941 was conducted by Poles, not by the occupying Germans who had instigated it.

This was a bold assertion in Poland, challenging the dominant view that only riffraff supported the Nazis and killed Jews, not people who knew and had relationships with them. Of course, nothing sells like controversy. Bookshops could not keep Neighbors on the shelves. A second print run was quickly ordered. While many Poles found the book shocking and offensive, for Jews who have read first-person accounts of Holocaust survivors – not to mentioned those whose loved ones and friends were from Poland and survived the genocide – likely the only shocking and offensive thing about Neighbors was the controversy. I myself had always assumed that collaboration between Poles and Germans during the Holocaust was a foregone conclusion, an idea I could not imagine to be offensive to Polish sensibilities. Ironically, as a result of reading the critique of Gross’ work, which posits a directly opposite view, I have begun to question my own assumptions. But before examining the reasons for this reevaluation, some additional notes on Neighbors are in order.

Situations of Extreme Choice

Neighbors generated so much debate that a text edited by Holocaust scholars Antony Polonsky and Joanna B. Michlic entitled The Neighbors Respond was published. The Neighbors Respond – both on its own and in tandem with Neighbors – provided a fascinating forum for Polish and Jewish writers alike. On the level of comparing "facts" of the story of Poland and the Holocaust, it introduced much to be compared and contrasted. For example, Gross placed the number of murdered Jews in Jedwabne at 1,600. A partial exhumation that took place as a result of Neighbors estimated the number of dead at 300-600. (An unfortunate and ironic aspect of the whole controversy was that the exhumation was not completed due to religious concerns raised by rabbis protesting the work). Despite discrepancies in the final tally between Gross' figure, an incomplete exhumation, and several new testimonies that have recently come to light, Gross has not altered his position. On a deeper level, the books have invited two passionately opposed schools of thought to elaborate on two radically different sets of collective memory. Regardless of the respective backgrounds of the readers, or the conclusions that they now hold, the most interesting result of the controversy is how it models the process by which history comes to be accepted based on the unique, or collective, agendas of historians.

For instance, this point was highlighted by Jolanta Zyndul – coordinator of the Mordechaj Anielewicz Center for Research and Education on Jewish History and Culture at the University of Warsaw founded 1990 – in a 2004 edition of Yad Vashem Magazine. Commenting on Holocaust historiography in Poland in general, as well as the Jan Gross controversy specifically, Zyndul explained:

Two years ago, the debate in Poland over Jedwabne –

instigated by Jan T. Gross’s Neighbors– facilitated a new

critical approach to the [Holocaust]. Until then, Polish

research had focused mainly on assistance to Jews in hiding

during the war. Today, we are also researching other, less

admirable actions of Poles during the Holocaust –

blackmailing Jews, informing on them to the German occupants,

and even murdering them.Obviously, the attitude of different societies towards the

extermination is one of the most crucial questions in Holocaust historiography. However, in Poland it overshadows all other

issues, such as the uniqueness of the Holocaust or its

interdependence with modernity. It also lacks – in my opinion

as a historian – an approach that portrays it as a universal

phenomenon where people face situations of extreme choice.

(emphasis added)

The key expression here is the “universal phenomenon where people face situations of extreme choice.” The situation in Poland – the “one of extreme choice” during the war – meant that Poles were viewed with contempt by both Soviet and Nazi occupiers who effectively split the country in half from August 1939 through the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact. Jews were, as is all ready well-known, also viewed with contempt. However, the Soviets found political use and offered privilege for a small percentage of Jews who identified themselves as communists. In this way, Nazis and Soviets created a hierarchy that pitted two traditionally rival groups against each other, effectively leading to the genocide estimated at 90 per cent of the Polish Jewish population and 20 per cent of the Polish Christian population. Understanding the function of these hierarchies is critical to understanding the controversy around the work of Gross as a whole.

Poles were treated as an inferior form of human beings to Germans under the Nazis, fit only for annual labor. Meanwhile Jews were not considered human at all. Given the historical context in which Poles were victimized by Nazis, it is easy to understand why Gross’ book, positing Polish-German collaboration as it does, strikes such a sensitive cord. Neighbors countered a hero-victim theme dominant in Polish Holocaust historiography – whereby Poles battled the Nazis and their policies on all fronts – that indeed needed to be challenged. More importantly, it highlighted how the Nazis used artificially created hierarchies to skillfully place one set of oppressed victims over another. A simultaneous status of oppressor and victim is not easy for most people to fathom. The all-too-human tendency to qualify people in wartime situations as heroes and villains, saints and devils, oppressors and victims meant that Poles had to confront the complex, often unpleasant, and often morally repugnant responses their grandparents had had to totalitarianism. Hence, Gross’s slim volume was not only threatening for exposing Polish anti Semitism. It also exposed the essential falseness of moral dichotomies in which people’s actions are only black or white or good or bad without shades of gray in between.

Judeo-Communists

In 1939, as mentioned earlier, Germany gained control of the West while the Soviets took over the East. Jews active as communists found opportunities under the new administration unavailable when Poland’s governing National Democratic Party, the Endecja, was in power. Prior to 1939, the only party in Poland that would accept Jews (so long as they were secular) was the communist party. According to Polish scholar Jerzy Jedlicki in The Neighbors Respond, this acceptance was a reversal of the “natural order” in which Christian Poles were traditionally ranked with a status above Jews. This meant that in 1941, when the Eastern half where Jedwabne was located was taken over by Germany, Jews were targeted by Poles and Germans alike.

Though communist Jews (as well as non-communist Jews who were accepted into administrative positions previously unavailable to them) enjoyed certain opportunities under the Soviets, the Soviets themselves were hardly Judeophiles. The newly established Soviet regime almost immediately set out to dismantle organized Jewish religious and political life, and Jews ultimately numbered a third of Soviet deportations. What emerges from a careful, dispassionate reading of The Neighbors Respond – particularly with regard to some of its more sympathetic historians – is a politically and religiously divided Jewish community that would have preferred Soviet rule over the Nazis for obvious reasons, but was confronted nonetheless with a terrible set of choices, none of which offered them any kind of respect or equality.

One can be certain that religious Jews, who made up a very large percentage of the Jewish-Polish population – and particularly traditional clergy and Hasidim – would not have supported the adamant secularism of the communists, hating the Soviets only slightly less than the Nazis. Despite this fact, the concept of Zydokomuna, the Polish term for Judeo-Communism, came to define Jews as a whole deep within the Polish psyche. A critique in The Neighbors Respond includes several pieces documenting Jews accused of collaboration with the Soviets, a traditional Polish enemy. What emerges then is one accusation of collective guilt (Jewish-Soviet) against another (Polish-German).