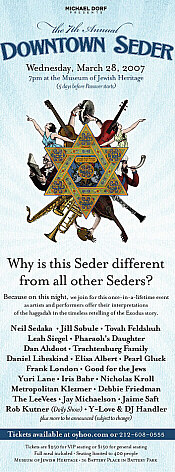

March 07

March 07

Keep Your Godwrestling, Thanks: The Uses and Limits of Theology

by Jay Michaelson

p. 2 of 2

3. ....and then there are the things we don't know that we don't know

The good news is that once the wrestling stops, you can let God win.

If there's one thing theology is useful for, it's negative theology: telling us that we don't know what we think we know. Think you know the purpose of life? You don't know. Think you know what God wants from you? You don't know. Think you know what God is, or that God is, or that what the word "God" even means? You don't know. And as soon as I don't have to know anything, the world opens up.

Let's try it.

That wonderful sense that you get when you make the world a little less painful for someone who is suffering - no, that's not God.

That sense of victory that you get when your team/nation/army/tribe wins its battle - nope, not God either.

The promise-keeper of Israel, the smiter of enemies, or, on the other side, that powerful moral imperative, that causes you to know, deep in your guts, what the right ethical choice is at any given moment - sorry.

All of these are myths, projections, hopes, and yearnings. Beautiful, but not "it" - at least, you can't prove it. Indeed, many theologians would say they can't be it, for various philosophical reasons. But leave that aside - let's just ask what you can know is true about God. Of course, the answer is nothing.

Here's a simple way to remember it: As long as God is everything and/or nothing, we're doing fine. It's when we think God is something that we've gotten into trouble.

Good? Powerful? Male? Ineffable? All concepts, all projections. In a future essay, I'll talk about this in more detail - how Kabbalah, beginning from a place of nonduality, ends up in a place of polytheism, and brings all these concepts back into the religious worldview. For now, it's just useful to remember that, if we just ask carefully what it is we actually know, we instantly disabuse ourselves of all the lousy ideas we project up into the heavens. How do you know that God wants a gentler world, but doesn't want child sacrifice? You don't - you just want it one way and not the other. How do you know that God loves Israel, and not the Palestinians? Same reason. How do you know God loves all people equally, regardless of nationality? Again, you don't. How do you know that God did or didn't write the Torah? You get the point.

Good? Powerful? Male? Ineffable? All concepts, all projections. In a future essay, I'll talk about this in more detail - how Kabbalah, beginning from a place of nonduality, ends up in a place of polytheism, and brings all these concepts back into the religious worldview. For now, it's just useful to remember that, if we just ask carefully what it is we actually know, we instantly disabuse ourselves of all the lousy ideas we project up into the heavens. How do you know that God wants a gentler world, but doesn't want child sacrifice? You don't - you just want it one way and not the other. How do you know that God loves Israel, and not the Palestinians? Same reason. How do you know God loves all people equally, regardless of nationality? Again, you don't. How do you know that God did or didn't write the Torah? You get the point.

We all have preferences about how the world should be, and some of those preferences definitely seem better to me than others. Some of them, after all, are tested by reason, and by moral conscience, and by a thousand other ways to sift mere preference from authentic moral sentiment. But all of that takes place prior to the projection of moral sentiment upon this or that sacred text. What does "Judaism" say about social justice, anyway? That you should feed the naked - or slaughter all the non-Israelite tribes? That everyone is responsible for everyone else - or that the wicked must be judged for their bad deeds, regardless of what "made them do it"?

Even Kant couldn't quite get the categorical imperative to hang on anything but skyhooks. (For Kant, it just seems so right, rationally speaking of course, that it has to be right; certainly more reflective than the Molech-worshipper, but different in kind, or degree?) So let's stop kidding ourselves. We should all do our best, developing the moral sentiments, nurturing compassion, cultivating critical thinking - all the things that help us make kind and wise decisions (and not coincidentally are in short supply in a political class beholden to dogma, faith, and authority). But let's leave God out of it. We don't know anything about the purposefulness, purposelessness, godlessness, or godfulness of the cosmos. We can't even figure out how to manage our own little corner of that cosmos without burning it up in carbon dioxide, for crying out loud - do we really think that we're capable of deducing, somehow, the point of it all? Please, negative theology, come and save us. Remind us that we have no idea. We have beautiful minds, hearts, and bodies - but they all have their limits.

The non-knowledge of negative theology is really something. Really something. Suppose you went through the day doubting every non-perceptual idea that you have. Not just the God stuff - but everything: politics, fashion preferences, how people are supposed to behave. It's not that you don't have these ideas, and act on them sometimes - it's just that you're not so sure. Would that lead to more conflict, or less? Would you be more open to the impressions of the world, to the daily music of humanity, to the power of Nature, or less? Would you be more detached, or more engaged?

Sometimes, the myths of Judaism help me to feel wonder. Other times, it's sometimes easier to say "I am grateful to the earth, air, fire, and water that created this food" than it is to bench birkat hamazon. Both feel ok, since I really have no idea. I don't even know what I don't know.

I'm not proposing anything radical - just letting the heart have its place and the mind its. Let's not have the mind pretend to have anything to say, really, about the essence of religion; let's let the heart soar. And, conversely, let's not pretend that the heart's yearnings about God have anything to say about how the world should be - let's leave that to calm and rational reflection, coupled with human moral sentiment. Wouldn't we all get along better, and be more honest with ourselves, to boot?

Or would it be just too terribly embarrassing, to admit that we choose God out of love and not reason?

Jay Michaelson is the chief editor of Zeek. He is the author of God in Your Body: Kabbalah, Mindfulness and Embodied Spiritual Practice.