September 07

September 07

We Ourselves Are to Blame: Hannah Arendt’s Jewish Writings

by Zachary Braiterman

p. 2 of 2

It was not the rejection of Judaism as a religion, as suggested by Ron Feldman in the introduction to the volume, but rather this public act of judgment in the New Yorker that was the final sticking point that caused so much pain and fury in the Jewish community, and which caused her such an “image problem” among her fellow Jews. “Concerning these arguments we are entitled to pass judgment,” Arendt contended to Scholem in their widely circulated exchange of letters about the Eichmann report. What gave her the confidence to pass such judgment was the strange argument that the Jewish leadership in the ghettos did not make decisions under the “immediate pressure and impact of terror.”

In his biting letter, Scholem had written: “There is something in the Jewish language that is completely indefinable, yet fully concrete – what the Jews call ahavath Israel, or love for the Jewish people. With you, my dear Hannah, as with so many intellectuals coming from the German left, there is no trace of it.” In reply, Arendt was more than happy to eschew any such “love,” which she caustically reduced to the worst elements of nationalism. Scholem may have missed the mark, since his appeal to "ahavat yisrael" violated the basic privilege placed on individual responsibility in Arendt's thinking. But Scholem was right to miss in Arendt another more basic Jewish virtue. She lacked the  attribute of rachmones (compassion, mercy), to the extent that she pitilessly blurred the distinction between victims and persecutors.

attribute of rachmones (compassion, mercy), to the extent that she pitilessly blurred the distinction between victims and persecutors.

What grieved Arendt, we learn from her letter to Scholem, was “the wrong done by my own people” more than “the wrong done by other peoples.” On principle there is nothing wrong with this fine thought. But did the sentiment square with the case at hand? It is safe to assume that in this asymmetrical order of wrong (the Nazi act of genocide compared to the victim’s failure of political leadership), it was the former that preoccupied Scholem and Arendt’s many other critics more than the latter.

Was Arendt “malicious,” as Scholem called her? Probably not. Was the rejection of Arendt by her people as “entirely unwarranted” as Jerome Kohn claims in the preface to the volume? Probably not. Arendt complained bitterly about the “incredible propaganda” directed against her in the wake of the Eichmann controversy. That she seems to have been genuinely surprised by the critical response suggests an extraordinary naiveté.

At any rate, it is here we begin to hear contemporary echoes – today when critics in or at the margins of the Jewish community stand up to slaughter sacred cows as a public act of individual conscience and then complain when self-appointed defenders of the faith (“the Israel Lobby”) “conspire” to “silence” them.

Having come full circle after Camp David and the September 11th attacks, there is something depressingly déjà vu about The Jewish Writings. Caught between narrow nationalism and internationalist pipe dreams, Arendt’s Zionism articles seem to flash forward to our own times,  making them look all the more hopeless. The arguments about the Eichmann book echo arguments between “the critic” and “the community” that are no less endless. Though they provide clear theoretical principles, Arendt’s writings end up clarifying little in practice.

making them look all the more hopeless. The arguments about the Eichmann book echo arguments between “the critic” and “the community” that are no less endless. Though they provide clear theoretical principles, Arendt’s writings end up clarifying little in practice.

Against such a pessimistic reading is the more likely possibility that our own times are in fact not as grim as Arendt’s. No matter what their opponents on the left and the right might think, George Bush is not Hitler, and neither are Osama bin Laden, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, or Khaled Meshal. And despite appearances to the contrary, criticism bears much less of a charge today than when the wounds from the Holocaust were still fresh and misconceptions about the history of Zionism were much more entrenched. For all the intellectual energy exhibited in these essays, Arendt will not show us a way out of our own predicaments. She wrote for her times and we live in ours.

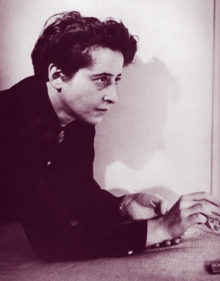

Still, Arendt’s Jewish writings leave us with two things to ponder now: The first is the call to couple individual conscience with the public face of politics – a fraught balancing act whose challenge Arendt posed so well, but which she so often bobbled. The second is the glorious image of Arendt herself. We come face to face with the persona cultivated by herself and by her admirers in the extraordinarily handsome photograph of her that stares back at us from The Jewish Writings’ dust jacket.

Still, Arendt’s Jewish writings leave us with two things to ponder now: The first is the call to couple individual conscience with the public face of politics – a fraught balancing act whose challenge Arendt posed so well, but which she so often bobbled. The second is the glorious image of Arendt herself. We come face to face with the persona cultivated by herself and by her admirers in the extraordinarily handsome photograph of her that stares back at us from The Jewish Writings’ dust jacket.

It is possible, of course, to alter an image, to damage a reputation, to impugn motives. Against an image, however, it is difficult to argue. The image of Arendt – the pariah personified, the émigré who lost her country but not her culture and conscience – will always enjoy a certain allure. There is something pure and sublime in this picture before which even her critics might stand in some awe. She speaks for herself, advances offbeat opinions and arguments, and insists like Job on her own rightness before the force of overwhelming power – the very surface impression of innocence past which Arendt wanted to think.

Zachary Braiterman teaches modern Jewish philosophy at Syracuse University and is the author of (God) After Auschwitz: Tradition and Change in Post-Holocaust Jewish Thought and The Shape of Revelation: Aesthetics and Modern Jewish Thought .