September 07

September 07

Trudy’s Wedding

by Jon Papernick

p. 2 of 3

Rabbi Judah Greenfield, Michael’s boyhood rabbi from Central Synagogue in Manhattan, his retirement suspended for the day, called the couple to stand before a low table where the Ketuba was spread out.

“What happened to your face?” Trudy said softly.

“I cut it shaving. Three hours ago.”

Tall, slim, and white-haired, the revered Rabbi Greenfield called forth the witnesses. Simon Levy stepped forward. And so did Uncle Izzy.

“Neither of you are blood relatives?,” Rabbi Greenfield asked.

“Of course I’m a blood relative, Greenfield,” Izzy boomed. “I’m his fucking uncle.”

“The Ketuba witness must be someone who is not a blood relative,” Rabbi Greenfield said evenly, wiping his brow. “The Ketuba witness must be someone who has not taken payment, and who has the vested interest of the sanctity of the marriage at heart.”

“Here we go,” Bobbie said.

“Izzy, go stand next to Max,” Trudy said.

“Listen, doll. I love you like a daughter and Michael like a son…”

“Come on, Iz,” Max beckoned, “Forget about it. Let the kids go.”

“…I was at his birth, his goddamned bris, his bar mitzvah, and now I’m going to witness this simcha, even if I drop dead.”

Trudy could see the veins pulsing on Izzy’s neck, sweat pouring from his face. She imagined a gondola on the Grand Canal. Michael put an arm around Izzy, “It was a mistake. We didn’t know. But you still get to say the motzei.”

“That true, Greenfield?”

The rabbi said nothing.

“Am I still in with the bread?” Izzy asked.

“Give him the bread and let’s get on with this,” Bobbie said, fanning herself with a wedding program.

It was agreed. Uncle Izzy would say the blessing over the bread. Simon ran up to the house to get Trudy’s best friend, Tammy, to stand in as the second witness.

Finally, everybody was ready. Rabbi Greenfield nodded his head at Trudy and Michael and began. “This is an important part of the Jewish life cycle in the eyes of the Jewish people and in the eyes of God…”

Through her peripheral vision, Trudy could see Michael’s jaw tense at the mention of God

“…continuing the tradition of your ancestors. By signing this Ketuba, you are entering into a sacred union before the community and God.”

“I can’t believe he mentioned God,” Michael said, after the signing, after Izzy had stalked back up the hill, after kissing all the women, and shaking all the hands.

Michael kissed Trudy and said, “I have to talk to him.”

Rabbi Greenfield, looking frail for the first time, withered from the heat said, “Well, Michael.” The rabbi offered a handshake and pulled Michael into a warm embrace. “I’m proud of you.”

“Rabbi,” Michael said, “Remember when we spoke after I got engaged and you promised not to mention God at my wedding?”

The rabbi looked surprised, and dabbed at the blood on Michael’s cheek with a handkerchief.

“I’m a cultural Jew in the humanist tradition,” Michael continued.

“Michael, I’ve known you a long time, through every phase of your life. And the one thing that has been consistent through all the haircuts and girlfriends, trends, and jobs good and bad, is your sense of humor. Please tell me you haven’t lost your sense of humor.”

“But you promised not to mention God.”

Rabbi Greenfield took Michael by the hand and said, “It would even have been okay for you to have worn your African robes. But asking a rabbi to not mention God is like asking a baker to not use dough. God is not going anywhere. I’m going to mention him during the ceremony. He’s in all seven blessings and I’m going to mention him some more as well. So let’s get out of this sun and get you married.”

After some bargaining, Rabbi Greenfield agreed to say the seven blessings in English, leaving Hebrew, the ancient language, out of all the prayers. Aside from Grandma Dot misplacing the wedding bands with her heart pills and Trudy nearly fainting under the chuppah from the heat, (even her web-thin veil felt as smothering as a blanket) the ceremony was perfect.

Rabbi Greenfield concluded the ceremony by saying, "In these trying times, with evil in the ascendancy, it is more important than ever to continue the traditions of your people.” Rabbi Greenfield placed a glass at Michael’s feet.

“Many reasons are given as to why we break a glass at a wedding. It is told we are to remember the destruction of the Temple many years ago in Jerusalem. Some say that we break a glass so that your love should endure as long as it would take to put the glass together again."

Uncle Izzy called out, "Even longer!"

Cheers rose up a dozen rows back. Trudy turned to Michael and could see his eyes glazed with tears of happiness, and a pink stream of blood oozing from his cut.

"Others would say that we break the glass to set perspective, to know that just as there is sorrow there is happiness and vice versa.” The rabbi paused. “The journey starts here, the dance begins here, to continue, God-willing, forever."

And at the signal from Rabbi Greenfield, Michael stomped the glass as hard as he could. The crowd shouted, "Mazel Tov," and they were married.

The guests had some difficulty finding their seats after the ceremony. Trudy had written out the guest’s names on a film of rice paper attached to folded card stock and had it arranged on a table by the entrance of the tent but, had forgotten to use indelible ink.

"I can't read the cards," one of Esther's friends said, tilting her bifocals down onto the bridge of her nose. "They're blurry."

"I can't read them either," Trudy’s former crush, Steve said.

The carefully-written names had expanded in the humidity like a sponge in water, bleeding into each other like a shrink’s file of Rorschach tests. Jefferies, the painter, planted himself at Table One and began wiping the sweat off his bald head with a cloth napkin destined for Trudy's mother. Each member of Michael's family sat at separate tables with their backs turned stubbornly to each other. The band climbed onto the stage and began its sound check, singing the chorus to, "Land of 1000 Dances."

"It's a zoo," Trudy said squeezing Michael's hand.

Order was eventually restored, after Michael deputized a half dozen of his friends to seat the guests in a close approximation of what Trudy had planned all those months ago.

Finally, a loaf of challah was wheeled in on a cart and Trudy's friend Tammy appeared at the front of the tent wearing her version of a flapper outfit.

"Is this on?" she said into the microphone.

"Yes!," people called from throughout the tent.

"I apologize for the technical difficulties," Tammy said, laughing awkwardly, her lips muffling against the microphone as she spoke. Trudy waved her to lift the mic farther away from her mouth.

"And now, without further ado, everybody's favorite uncle... Izzy!"

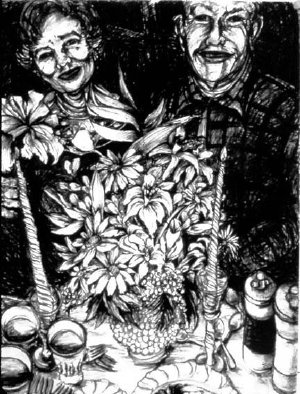

There was a smattering of applause throughout the tent. It seemed to Trudy that there were several different parties going on at the same time, and that her and Michael's friends at the back of the tent were more interested in the sprinklers that had just come on to water the verdant grass. Sitting at the small bridal table with her new husband, not far from the glazed challah, Trudy saw Uncle Izzy, his jaw jutting forward proudly like a Mussolini portrait, his silver flat-top, proudly standing at attention, step up to the microphone and offer a curt, "Hello." He then mumbled the prayer over the bread in his Lower East Side Ashkenazi-accented Hebrew and began to cut the bread with great Grandma Mindel's marble-handled challah knife.

Something's wrong, Trudy thought watching Izzy sawing away at the bread. His eyes rolled back in his head, showing only the whites. He sawed for another second, maybe less, then dropped to the floor, his arm still moving up and down with the blade in his right hand.

Esther's best friend Rhonda Katz stood up in her seat and broke a stunned silence, shouting "Oh my God. He's dead!"

A collective gasp rose up from the front half of the tent; Trudy and Michael's friends, oblivious, running through the sprinklers outside the tent.

"Somebody call a doctor," Trudy shouted. "What do we do?"

Max Sherwood sat stricken in his seat as his only brother lay on the dance floor, his arm moving mechanically, the knife blade slicing through the air. Izzy's oldest son's wife Sarah was a doctor. Izzy hadn't spoken to either of them in almost ten years because of some long-forgotten perceived slight. And there she was running along the dance floor in her heels, dropping to her knees and performing artificial resuscitation on the putative family patriarch. Izzy's arm continued to slice up-and-down as Trudy and Michael and the rest of the family gathered around Izzy's splayed body. Trudy wondered whether Izzy had soiled himself because he stank like dirty laundry.