January 08

January 08

What Independent Minyanim Teach Us About the Next Generation of Jewish Communities

Ethan Tucker

In the last decade, a host of independent minyanim have sprung up in Jewish communities in North America and throughout the world. While the overall number of people involved in these minyanim remains a tiny percentage of the Jewish population at large, there is no denying that these emerging communities have already had an impact on the way Jews - in particular younger Jews - are thinking about Jewish communal life and commitment.

In the last decade, a host of independent minyanim have sprung up in Jewish communities in North America and throughout the world. While the overall number of people involved in these minyanim remains a tiny percentage of the Jewish population at large, there is no denying that these emerging communities have already had an impact on the way Jews - in particular younger Jews - are thinking about Jewish communal life and commitment.

Independent minyanim, diverse in their practices and religious assumptions, have initiated a structural revolution, rather than an ideological one. That structural revolution has included certain assumptions about what makes for a compelling Jewish life, how normative questions ought to be addressed, and what it means to empower individuals and communities to live out a religious vision. But a prayer community is ultimately only one slice of Jewish life. In this essay, I will examine the realities that produced these independent minyanim and propose a broader vision for extending this structural revolution so that it can have an impact on numerous other areas of Jewish life.

I begin with noting the following three critical facts that must, I believe, form the starting point for any vision of Jewish life in the contemporary world:

Jews live modern, autonomous lives outside of the sphere of coercive rabbinic power (at least outside of the State of Israel) and thus will make their own normative choices - including the choice to empower others to make decisions.

Jews are increasingly highly educated, possessing a college degree or higher, and have thus been trained to think critically about texts (non-Jewish ones, at least) and to evaluate them as potential sources of wisdom rather than as self-evident sources of authority.

Despite the challenges from modernity, many contemporary Jews care deeply about what Judaism has to say about challenges great and small and actively seek traditional language for grappling with their personal and communal concerns.

In this reality, Jewish life must do three things if it is to flourish and succeed: 1) it must be compelling and of excellent quality, so that people will choose it; 2) its discourse must be serious, honest, adaptable, deep and transparent, so that it can provide spiritual guidance that truly responds to spiritual seekers; and 3) it must empower people and communities in order to create the motivation and the resources to perpetuate the full gamut of Jewish life. While Jewish life in the modern world has focused on ideological commitments (such as the authority of Jewish law or the nature of sacred text), the above factors are primarily structural, rather than ideological, and will be discussed in turn. First I will discuss the values in theory and then apply them to particular practical examples.

Excellence

To the extent Jews yearn for Jewish life, it is because they yearn for its potentially powerful and transformative message. Earlier generations, by force or by choice, may have sought Jewish connection out of familial, economic, social, and communal interests. Today, however, those younger Jews who do choose Judaism do so because of the merits of what it has to offer intellectually, spiritually, and emotionally. The success of many independent minyanim has been in providing a moving prayer experience that truly immerses people in davening and invites them to think further about their own spiritual quest in the context of community. Beyond prayer, the rhetorics of global obligation, Jewish social responsibility, and God’s covenantal relationship with human beings are all critical, but the essential point is in translating the ideological message into a concrete, compelling experience. How can the success of independent minyanim inform such an effort?

First, an emphasis on quality. Educated Jews, most of them in urban centers, have come to expect excellence in their intellectual, cultural, culinary, aesthetic, and even recreational lives. Independent minyanim have recognized that a key element of their success is their ability to deliver quality davening, Torah reading and teaching as part of their services. More broadly, this means that anything the Jewish community does must be held to the highest standards in order to attract those with the freedom to choose other options. Tribal loyalty to Jewish institutions has ebbed, and while the language of consumerism may be antithetical to some aspects of spiritual life, it nonetheless informs how young Jews select among multiple offerings; they want the best Jewish product available. For example, Jews who used to settle for standard melodies on Friday night will flock to a start-up minyan featuring new and unfamiliar melodies if the musical experience speaks to their soul. And a well-structured class that is thoughtfully tailored to students’ needs and expectations will beat out an unreflective presentation by a more seasoned educator every time.

Second, an avoidance of being defined by unnecessary ideological boundaries when practical coexistence is possible. Part of the success of independent minyanim is driven by their unwillingness to affiliate officially with existing religious denominations, an unwillingness that has enabled them to embrace all who are interested in the minyan’s concrete practice. Instead of confronting people with an ideological choice, independent minyanim have, for the most part, simply invited people to join their specific synagogue practices. This model urges a pragmatism that transcends pluralism: build a Jewish community with a specific set of practices rather than open an ideological conversation that is bound to emphasize differences that will impede the launch of a successful, cohesive community. Ultimately, the best way to address difference in the Jewish world is to create competing and complementary communities rather than by building overbroad coalitions that stifle creativity and breed frustration and resentment. Emerging Jewish communities must emphasize their distinctive substance over institutional loyalty.

Seriousness, Depth, Honesty and Transparency

People choose to engage with Judaism because they specifically want a millennia-old religion, as opposed to a non-religious social group, or an ideology which reflects contemporary values alone.  Most newer independent minyanim are significantly more emotive and traditional in their prayer experiences than are most non-Hasidic synagogues. Similarly, when Jews ask spiritual questions of Judaism, they are doing so because they are seeking answers that will tie them in to the ancient conversations of our people. If they wanted purely contemporary answers, they would consult purely contemporary sources. Instead, by choosing to ask Jewish questions, they want to know how voices from other times and places might guide them in their religious quest. They want the intensity of engaging with all layers of Jewish history, knowing that this process will make them wiser and more thoughtful about their practice and belief. In short, they seek the guidance of the Jewish discourses of Torah, aggadah, midrash and halacha.

Most newer independent minyanim are significantly more emotive and traditional in their prayer experiences than are most non-Hasidic synagogues. Similarly, when Jews ask spiritual questions of Judaism, they are doing so because they are seeking answers that will tie them in to the ancient conversations of our people. If they wanted purely contemporary answers, they would consult purely contemporary sources. Instead, by choosing to ask Jewish questions, they want to know how voices from other times and places might guide them in their religious quest. They want the intensity of engaging with all layers of Jewish history, knowing that this process will make them wiser and more thoughtful about their practice and belief. In short, they seek the guidance of the Jewish discourses of Torah, aggadah, midrash and halacha.

Of all these, halacha in particular gets a bad rap, primarily because of specific holdings and conclusions that some find objectionable or problematic, as well as because of its propensity to overly legalistic conversation. But as I am employing the term, halacha refers to the shared spiritual discourse of mining the Jewish past for insight and wisdom, without assumptions of how the discussion will conclude - or whether it will conclude in the same way for everybody. It thus ought to be applicable to a vast range of possible Jewish communities - not just those conventionally referred to as “halachic” - ultimately including any community that wants to bring the discourse of halacha to bear on contemporary Jewish life. The details always come out differently in different conversations, but the assumption that we seek normative guidance from our tradition - that is, guidance on how we ought to live - is, I think, at the heart of any engaged, thoughtful and self-reflective Jewish community, “halachic” and otherwise.

These discussions, like our recourse to all of our texts and narratives, must be honest and transparent. Jewish learning environments must welcome all well-intentioned questions and challenges and engage them seriously. We must give meaningful responses to critiques that neither appeal to opaque textual authority (“the Shulhan Aruch says so”) nor enforce communal boundaries (“this movement has taken a stand, if you don’t like it, leave”) in order to shut down discussion. Rather, we should be seeking to convey the values that undergird various texts and communal decisions and to communicate these to (and have them refined by) people who challenge them as not being immediately intuitive.

Empowerment

Empowerment must be present on two planes: individual and communal. On the individual level, it means giving free market Jews the motivation to engage with Jewish life by giving them the tools they need to participate in prayer, study and social justice. When Kehilat Hadar offers a class on how to do hagbahah - lifting the Torah Scroll at the end of the reading - it is making a strong statement that this skill is not esoteric, and reserved for the elite, but open to all who are willing to put in the (relatively minimal) time required to learn it. Similarly, learning programs that emphasize not just Jewish content but text skills both expand the pool of active learners in a Jewish community, and send a strong message that these skills are accessible to any Jew willing to invest in them and imply an expectation that the most committed members of the community will indeed make this investment.

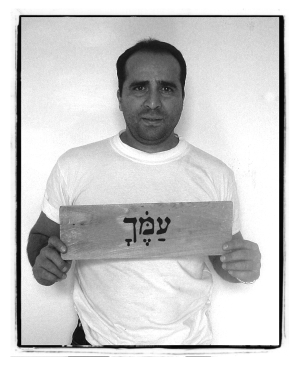

There is also empowerment on the communal level, by which I mean a community’s ability to provide all the basics of Jewish life for itself and to pass on the skills and infrastructure to subsequent generations. Here, the model of religious kibbutzim in Israel is instructive, where kibbutz members write their own megillah for Purim, often bake their own matzot for Pesach, and may even have a member who gets trained as a scribe in order to write or fix Torah Scrolls or mezuzot for the community. A critical aspect of communal empowerment is a sense of self-sufficiency and a feeling that one does not need to turn to other Jews in otherwise secluded communities with whom one has no relationship in order to preserve the basics of Jewish life. We all cook and bake. Why shouldn’t every community be making its own matzot? We all know people who can write beautifully. Why shouldn’t they learn to write our sacred texts? Not only is the empowered community richer, it is also more self-confident, as it knows that its self-sufficiency entitles it to a place at the table with any other Jewish community in the world and throughout history.

There is also empowerment on the communal level, by which I mean a community’s ability to provide all the basics of Jewish life for itself and to pass on the skills and infrastructure to subsequent generations. Here, the model of religious kibbutzim in Israel is instructive, where kibbutz members write their own megillah for Purim, often bake their own matzot for Pesach, and may even have a member who gets trained as a scribe in order to write or fix Torah Scrolls or mezuzot for the community. A critical aspect of communal empowerment is a sense of self-sufficiency and a feeling that one does not need to turn to other Jews in otherwise secluded communities with whom one has no relationship in order to preserve the basics of Jewish life. We all cook and bake. Why shouldn’t every community be making its own matzot? We all know people who can write beautifully. Why shouldn’t they learn to write our sacred texts? Not only is the empowered community richer, it is also more self-confident, as it knows that its self-sufficiency entitles it to a place at the table with any other Jewish community in the world and throughout history.