December 08

December 08

Jewish Architecture: An Interview with Daniel Libeskind

Jo Ellen Kaiser

Wowed by the example of Frank Gehry’s Bilbao Guggenheim, museums around the world have raced to commission brilliant, experimental architects to build structures at least as noteworthy as their collections. Architect Daniel Libeskind has become the star of the Jewish museum world with his stunning designs for the Jewish Museum Berlin, Danish Jewish Museum, and now the San Francisco Contemporary Jewish Museum.

Unique in being a museum without a permanent collection, the San Francisco Contemporary Jewish Museum has, for over twenty years, devoted itself to exhibitions that explore contemporary perspectives on Jewish culture. Libeskind’s new building, opening June 8, 2008, will allow the museum to remain flexible in defining Jewish identity by offering a variety of differently shaped and purposed spaces, including ones specially designed for music, film, and hands-on art education, as well as the more typical white-wall galleries.

Daniel Libeskind has become best-known for winning the World Trade Center design competition (and the resultant brouhaha). Yet his most important work may well be found elsewhere, ranging from the severe angles and sharp edges of the Royal Ontario Museum to the graceful, curving, almost bowed forms of his Reflections project in Singapore to the San Francisco museum with its almost aggressive blue beacon jutting out from the shell of an old water pumping station.

Zeek talked with Libeskind about creating a specifically Jewish space for the San Francisco museum in the conversation that follows.

|

|---|

Daniel Libeskind |

Zeek: I’ve had an opportunity to tour the Jewish Museum of San Francisco and I was very impressed—the spaces are complex visually and yet open and inviting. I understand they are deeply symbolic, with a physical “chet” and “yud”—the word Chai-- defining the space. Can you talk about the design for our readers?

Libeskind: I conceived the project as a new Jewish institution that is looking forward and celebrates life. And what better emblem and symbol of Jewish culture and identity than life itself? That is what Judaism is all about. So I created a museum which is almost an illuminated manuscript in three dimensions, which in its margins interacts with others’ history, the history of the power station [which was already on the site and is incorporated into the design], the history of Yerba Buena Gardens [the site], the history of the Bay Area. The building in itself is a conversation with different levels of history.

Zeek: I noticed that this museum differs from the Jewish Museum in Berlin or the Danish Jewish museum, both of which you also designed, in that those museums look backwards while this one looks forward. In fact, it only looks forward, since it doesn’t have any permanent exhibits. I was interested in your understanding of a Jewish identity that is not connected to a Jewish past, and what the challenge was for you?

Libeskind: This project was very different from my Jewish projects in Europe, because those always have the memory of the destruction of European Jews—that is part of the dark history of Europe. That is certainly not the case in San Francisco and America. So this building is a celebration of America, American Jews, American openness, and the vitality of the Jewish community in America. In that sense, you are right, it is a museum that really looks forward. But I would say it is still based on emblems and symbols that are rooted deeply in the Jewish tradition. The inextinguishable light of the building itself, and the meaning of those Hebrew letters, is not just symbolic or metaphorical--you cannot disassociate the symbols from the meanings they contain, which is quintessentially Jewish as well.

|

|---|

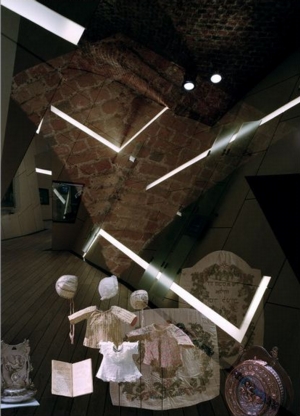

Libeskind's design for the Contemporary Jewish Museum of San Fransisco |

Zeek: As you are talking, it seems that one of the challenges was the challenge of working in an interfaith environment without assimilating.

Libeskind: Absolutely. The building had to grow out of a turn of the nineteenth century building, a power station, and also the bottom of a twentieth century hotel [the Jewish museum shares a basement and carves a first floor room space from the Four Seasons hotel next door]. Then the building needs to find an identity that is not compromised, not blending in, but cutting across these existing structures and establishing an identity that is not ambiguous.

Zeek: A lot of people have suggested that Jewish identity is undergoing a fundamental transformation post-Holocaust and post-State of Israel; some people say that Judaism itself is post-diasporic and we need to have a new idea of what it means to be a Jew. I was wondering if you had been engaged in these ideas and how you see Jews and Judaism in the 21st century?

Libeskind: That’s a great question. I can only answer for myself. For many complex reasons the Jewish world has become very polarized. We have on one hand a growth of religion, a growth of the religious movements, and on the other hand we have the increasing assimilation of Jews. For me, the 21st century is about bringing back to the center a Jewish identity, an identity that is free, that is open, that is complex.

Zeek: So what you are doing with this museum is creating spaces that have a kind of ambiguity to them—they can become anything. I am thinking particularly of the auditorium space. There is flexibility built in.

Libeskind: Absolutely, flexibility and fluidity. At the same time, each of the spaces is not just iconic superficially, by its shape, but because they are rooted in other dramas of Jewish history—the drama of contemporary Israel, the drama of what the synagogue means, the drama of Talmud and its commentaries. It’s a break in space.

It’s certainly true that for so long, it was a cliche that Jews were not a visual people. That Jews were forbidden to engage in spacial affect. But that’s certainly not true. If you go to the biblical text, we know there are the cherubim in the Temple, we know there was a rich visual world. It was not the world of pagan idolatry, but it communicated to people.

|

|---|

Jewish Museum Berlin (Juedisches Museum Berlin) |

Zeek: Yes, there’s a huge section of Torah devoted to describing spaces.

Libeskind: And very rich spaces. Jews are so implicated in architecture. Such great chapters are devoted to the tabernacle and the Temple and the ark and the eruv, because space and what it means is so importantly embedded in Jewish memory. In a sense this is a presentation in contemporary terms of a very historical topic.

Zeek: I had a question about the beautiful blue tiles you used on the new parts of the facade. They made me think of water. When I think of a Jewish element, I usually think of fire.

Libeskind: Fire, but you also have to think of revelation, which is blue. It’s not a coincidence that tallit are white and blue, that the State of Israel’s flag is white and blue. The blue is not just a naturalistic idea of the blue that comes from the tallit and from water. It comes from the idea of eternity, of coming out of blue into reality.

Zeek: As you talk, you talk about the fluidity and transitory nature of the space, and you also talk about eternity and the things that remain unchanging, and that tension seems very essential to an ancient religion like Judaism.

|

|---|

The Danish Jewish Museum (Dansk Jodisk Museum) |

Libeskind: That’s a good way of putting it. I think the reason Judaism is open is because it is based on something eternal. Because freedom is built so deeply into the Jewish tradition, everything is new, everything is possible.

Zeek: As a writer, that’s why I love the way our text is written over so many times, it’s very freeing. You have layers of text, which means you can keep writing on them.

Libeskind: Exactly. People coming to this museum will inscribe themselves into the text of the museum. By moving through the spaces of L’Chaim, each person will inscribe themselves in a unique way, through a text that is endless. That is part of the notion of the building. It is not just a plan, but a permanent encounter which depends on the participants to make it live.

Zeek: Thank you.

Jo Ellen Kaiser is the editor-in-chief of Zeek.