January 06

January 06

Dear Mr. Pinter

Dan Friedman

I am writing in response to your discussion of contemporary Anglo-American geopolitics and its relation to “truth” in your recent Nobel Lecture, “Art, Truth, & Politics." More particularly I want to begin to explain why many of your natural allies -- people who admire your work, see you as an ally in the ongoing fight for truth, integrity, and downright accountability in global democratic politics, and draw similar conclusions to yours about current U.S. foreign policy -- found your lecture unhelpful and, in places, misguided.

I am writing in response to your discussion of contemporary Anglo-American geopolitics and its relation to “truth” in your recent Nobel Lecture, “Art, Truth, & Politics." More particularly I want to begin to explain why many of your natural allies -- people who admire your work, see you as an ally in the ongoing fight for truth, integrity, and downright accountability in global democratic politics, and draw similar conclusions to yours about current U.S. foreign policy -- found your lecture unhelpful and, in places, misguided.

The first problem with your attack on the current situation is that you offer no alternative -- either to the U.N. or to the way that the United States has exercised its de facto leadership of the community of nations. The exercise of military and political power is always, and necessarily, marked by compromises. Today's United Nations, although it seems deeply flawed, is an attempt at structuring those compromises in meaningful political time, and with the possibility for the different sides to be heard. What is your proposed alternative? While perhaps it is the place of an artist merely to comment on the present, rather than prescribe policies for the future, surely an immediate response to your critiques would be along the lines of Churchill’s comment about democracy – it’s “the worst form of government, except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.”

It is no accident that a writer who has spent as much time and energy on human rights as yourself should win the Nobel Prize for Literature this year, when those rights seem deeply compromised by those members of the world community who nominally defend them. Although I mean in no way to diminish your writing, your work for human rights in the past decades is as much the context of the prize as your considerable dramatic oeuvre. Even given these contexts the content of your speech was far from obvious – you had been given a platform but your decision to use it was brave. Yet without specifying any alternatives, or even reforms, your critics are given ample grounds to dismiss you (and, by extension, those of us who share your views) as overly critical and idealistic.

The second problem with your lecture is its lack of nuance with respect to its targets. At the start of Moses and Monotheism (1940) Sigmund Freud discusses the dangers of confronting “supposed national interests” to “deny a people the man whom it praises as the greatest of its sons.” Although he purportedly is “denying” the Jews' Moses (“the greatest of its sons”) by claiming that he was, in fact, an Egyptian, Freud’s analysis runs exactly counter to the essentialist Aryan views of the Nazis and their black-haired, brown-eyed leader. At once arguing against the Jews' enemies by undermining the Jews' own claims, Freud was as steadfast as yourself in his defence of truth. “No consideration,” he states in his opening paragraph “will move me to set aside truth in favour of supposed national interests.”

Yet whereas Freud never separated his subtle, pioneering work in psychoanalysis with from political concerns, you seem to be two different people -- a dichotomy you actually seem to support, as we will see below. You too set aside your own national interests as a subject of the United Kingdom, in order to speak what your perceive to be the truth, while attacking Bush and Blair, who are, in political terms, the greatest sons of the current world order. However, whereas Freud deployed his talents as an analyst to suggest a deeply critical alternative analysis of history that applied to his own time, there seems to be an explicit disjunction between your own plays – your area of excellence – and your treatment of contemporary events. As a playwright used to fleshing out multiple characters in your plays and discovering, by your own account, their voices as you wrote them, your Nobel Lecture was surprisingly univocal. Your disingenuous dismissal of the United States in its entirety ignores the extremely heterogeneous societies and histories in the United States, ones that have produced and inspired art and movements for peace, democracy, and liberation across the world.

Yet whereas Freud never separated his subtle, pioneering work in psychoanalysis with from political concerns, you seem to be two different people -- a dichotomy you actually seem to support, as we will see below. You too set aside your own national interests as a subject of the United Kingdom, in order to speak what your perceive to be the truth, while attacking Bush and Blair, who are, in political terms, the greatest sons of the current world order. However, whereas Freud deployed his talents as an analyst to suggest a deeply critical alternative analysis of history that applied to his own time, there seems to be an explicit disjunction between your own plays – your area of excellence – and your treatment of contemporary events. As a playwright used to fleshing out multiple characters in your plays and discovering, by your own account, their voices as you wrote them, your Nobel Lecture was surprisingly univocal. Your disingenuous dismissal of the United States in its entirety ignores the extremely heterogeneous societies and histories in the United States, ones that have produced and inspired art and movements for peace, democracy, and liberation across the world.

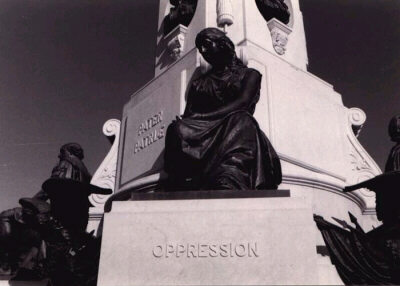

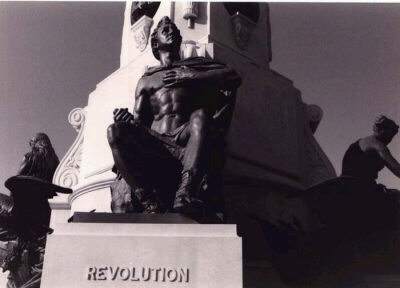

Both the United Kingdom and the United States have much to be proud of, but also much to regret, in their histories, cultures, attitudes, and actions. Moreover, as you note about truth and falsehood, negative and positive exist simultaneously, even paradoxically in symbiosis: one does not "outweigh" the other, nor does the negative "undermine" the positive. This is true not only in cultural terms but even in terms of power. For example, some of England's and the United States' most regrettable actions have come about as a result of the great power that these two English-speaking nations have had at their disposal over the past two centuries -- yet some of their greatest achievements have as well; for example, helping to bring about real democratic revolutions, from France to, more recently, the Ukraine. By dismissing the U.S. as entirely a power-hungry nation you put on the defensive the majority of its citizens who intend it to be, rather, a light unto the nations. Furthermore, in painting the nation with one colour in that way, you alienate exactly those constituencies you aim to mobilize – those who feel aggrieved at the actions carried out in their name.

It is the ideology that underlies this 'split personality' that is the third, and most central, problem with your lecture: namely, your differentiation between ideas of truth as a writer and truth as a citizen. For a writer you say (or quote yourself in 1958 saying) that “A thing is not necessarily either true or false; it can be both true and false.” This statement, you now claim, is not the case for a citizen who must rather ask: “What is true? What is false?” As you point out, the context of truth in art is quite different from the context of truth in politics. However, in both fields, the status of truth is of the utmost importance. Despite the absolute truth being unattainable (“Truth in drama is forever elusive”) – in life, as in drama – as you point out, “the search is clearly what drives the endeavour.” Furthermore it is only through the critical engagement of artist, politician, audience or critic that “you stumble upon the truth in the dark.” One must take a stand on representations in both cases, because both artists and politicians continue to shape our world much as they did in 1958.

The distinction between a citizen and an artist, or at the very least an art critic, has become smaller, not greater, since 1958. You talk about the political rhetoric of “the people,” employed especially by leaders of the United States of America, and criticize that same “people” for being quiet in the face of those atrocities of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries carried out in its name. There are three reasons for their quietude: first, diminishing access to information as power is centralized and concealed; second, insulation from the results of the atrocities; third the dilution of the important information that is available by the vast river of mediatized information. Despite the anti-democratic tendencies of the first of these, the third, diluting effect, disguises the fact that more and more information is potentially available to the people in whose name UN Security Council policies are carried out, but that information is delivered in increasingly artistic ways. Yearning for a return to some objective truth in reporting, or some objective truth in understanding, is misguided because those sorts of truth never existed and never will exist: power distorts the truth in the hands of an author quite as much as it distorts it in the hands of an authority.