August 06

August 06

Biography as Destiny: Eva Hesse at the Jewish Museum

by Esther Nussbaum

p. 2 of 2

| Continued...

Increasingly, scholars are seeking to ask how Hesse’s Jewish background might affect the way we can think about her work. Hesse was born in 1936 in Hamburg, leaving Germany on the Kindertransport to Amsterdam before eventually arriving in New York. Are Hesse’s works haunted by the Holocaust, and did her experience of displacement affect her art practice? In thinking through these and other questions, historians have tended to look at the implications of her return to Germany as a young artist, and to comments she made near the end of her life in which she related Carl Andre’s work to the floors of concentration camp showers. In the current exhibition at the Jewish Museum, the curators have for the first time displayed documents relating to her birth in Nazi Germany, and the Tagebucher (diaristic photo-albums) her father made for her in which her flight from Germany and arrival in New York is recorded. The curators display both her work and this documentary evidence, being quite clear to separate the biographical material from the galleries in which her work is shown. They acknowledge the necessity and difficulty of relating life to art, leaving the question of the relationship up for debate. Mark Godfrey is Lecturer in the History and Theory of

Art at University College London, his essay in the catalogue for the exhibition

discusses Hesse’s late hanging sculptures. |

To me, however, the attempts by art historians and critics to link Hesse's art to her experience of the Holocaust seem stretched. Indeed, over and above her artistic production, Hesse’s written and verbal legacy affirms that she was concerned with intellectual and philosophical aspects of the act of creation -- not with psychological catharsis. Nimser quotes Hesse as saying “when I work, it’s only the abstract qualities that I’m working with, which is to say the material, the form it’s going to take, the size, the scale, the positioning ….I don’t value the totality of the image on these abstract or esthetic points. For me it’s a total image that has to do with me and life.”

In 1961, Hesse spent 15 months

in Germany with her husband, sculptor Tom Doyle (they would divorce as soon

as they returned to New York). This was the turning point for Hesse. Doyle suggested

to her that she try her hand at sculpture using the materials (“junk”) that

were lying around in the unused factory that they were using as studios. Electrical

cord, plaster, string, wire, steel - all became the elements of her works and

eventually expanded to include rubber, fiberglass, plexiglass, and latex as

well as other industrial materials. Hesse employed papier mâché techniques to

create her sculptural pieces, all of which had specific placement in space in

the artist’s mind. She was also rather obsessive about titles and purchased

a thesaurus to play with conceptual words: “Accession”, “Accretion”, “Repetition”,

“Schema”, “Sequel” “Connection” “Several”, “Compass” hint at Hesse’s interest

in movement, change, and ephemerality.

In 1961, Hesse spent 15 months

in Germany with her husband, sculptor Tom Doyle (they would divorce as soon

as they returned to New York). This was the turning point for Hesse. Doyle suggested

to her that she try her hand at sculpture using the materials (“junk”) that

were lying around in the unused factory that they were using as studios. Electrical

cord, plaster, string, wire, steel - all became the elements of her works and

eventually expanded to include rubber, fiberglass, plexiglass, and latex as

well as other industrial materials. Hesse employed papier mâché techniques to

create her sculptural pieces, all of which had specific placement in space in

the artist’s mind. She was also rather obsessive about titles and purchased

a thesaurus to play with conceptual words: “Accession”, “Accretion”, “Repetition”,

“Schema”, “Sequel” “Connection” “Several”, “Compass” hint at Hesse’s interest

in movement, change, and ephemerality.

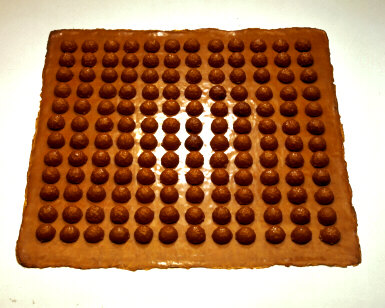

Each of the works in the exhibition demonstrates different aspects of the artist’s interests in materials. “Ringaround Arosie,” an early piece, uses raised forms of papier-maché wound cloth-covered electrical wire. “Accretion” consists of fifty tubes made of fiberglass and coated in resin. A complicated wrapping of paper tubes that are propped against a wall manage to seem both identical and individualized at the same time. “Schema” (shown here) is composed of 144 Spalding rubber balls covered in latex on a grid that relates to a rigid minimalist idiom. “Sequel” breaks the mold by giving the arrangement a randomness. At one point Hesse decided to hang her sculptures from the ceiling, as opposed to those deliberately grounded to emphasize their gravitational aspect.

Hesse’s statements at the time of her 1968 landmark exhibition entitled Chain Polymers (both latex and fiberglass are long-chain polymers – chemical compounds) at the Fischbach Gallery in New York sound almost Kabbalistic: “I would like the work to be non-work. This means that it would find its way beyond my preconceptions.” Or, “It is the unknown quantity from which and where I want to go.” Or, “In its simplistic stand it achieves its own identity.” Or “It is something, it is nothing.”

Despite the curatorial attempts to make some durable sense of her work, it is the random, chaotic aspects that dominate -- along with the sense of fragility. Critics have described some of her pieces as organic and anthropomorphic, but Hesse’s achievement lies less in their recognizable elements than in the confrontation with abstract, non representational forms that exist for her in a non-present universe. Seeing Hesse’s work today does not startle; when it was first exhibited it certainly did.

Still, the viewer today can still feel a sense of discovery in Hesse’s work, of seeing in imperfect forms and shaped objects daring feats of creativity in the imaginative fabrication of materials, use of scale and space. The pieces convey complexity and ingenuity, inspiring a contemplative interaction with the works.

There is, however, an atmosphere of memorial tribute in this exhibition: an homage to the artist that is somewhat oppressive. Because of the emphasis on her tragically short life and her personal misfortunes, the exhibit is less of a critical assessment of her art than an episode of "Behind the Sculpture." As for Hesse's Jewishness, the artistic impulse of creatio ex nihilo may or may not have been consciously Jewish, but the sculptures in the current exhibition, beautifully installed in the museum’s comparatively limited space, continue to captivate, perhaps because of her particular Jewish experience -- or perhaps regardless of it.

Of course, if Hesse's biography is not her destiny, then this is an exhibition at a Jewish museum that is devoid of Jewish artistic content. By way of response to this critique, I offer this excerpt from the 1976 catalogue The Jewish Experience in the Art of the 20th Century, an exhibit which coincided with the United States Bicentennial Celebration. In the prefatory remarks that could have referred to Eva Hesse, philanthropist Joy G. Ungerleider, the curator, wrote: “Ambiguity in defining the Jewish experience raises numerous possibilities…. Jewish artists have been drawn to the mainstream of 20th century art. Some will regard this participation as representing alienation from their Jewish heritage – others will regard it as an affirmation. The Jewish Museum believes that this is an historical phenomenon worthy of documentation.”

-----------------

The exhibition will be at the Jewish Museum until September 17th. Exhibition Curators are Elizabeth Sussman and Fred Wasserman. The Jewish Museum is located at 1109 Fifth Avenue, corner 92nd Street in New York City. For the first time in its history the museum has Saturday hours (with no admission charge). For more information, please log onto www.thejewishmuseum.org or call 212 423-3200. To see the online gallery click here

Esther Nussbaum, Director of Library and Media Services at Ramaz Upper School in New York City, has reviewed Jewish Art exhibitions for many years. She is the past editor of Jewish Book World, the publication of the Jewish Book Council.