Jay Michaelson

Jay MichaelsonWhat Turrell offers, however, is what art at its most profound should offer: a re-visioning of consciousness itself. Merely decorative art provides us with pleasant furnishings for our existing mental homes. Transformative art offers a different architecture. Sometimes this re-visioning is closely linked to a particular theory of perception (Seurat, Picasso/Braque, Baer, Turrell); sometimes it changes our experience of supposedly 'non-art' reality into an aesthetic moment (Cage, Warhol, Duchamp, conceptual art); sometimes art captures the poetry of moments that are otherwise so transitory as to escape notice entirely (Vermeer, Brueghel) or so sublime/terrible that they are reminders of the transcendent (German Romanticism, Picasso, Delacroix). And some art works purely symbolically-psychologically, involving our deep, emotional selves in a visual experience (Rothko, Pollock). In all of these cases, art is a form of contemplative practice, taking us out of mundane consciousness and into a mind-state in which the conventions of the quotidian may be seen as the contingent ephemera that they are. Even when art seems to lose itself in theory, its essential newness means that the boundaries of experience are forever being expanded. Definitions are always inadequate; the numinous is always evoked.

Most overtly 'spiritual' art is less than this. Typically, it more

closely resembles a cliched repetition of 'spiritual' imagery: visual

cues from religious traditions, symbolic structures from mysticism. Its experience is

secondary. We respond to these cues (if at all) not because they embody the numinous but merely

because they refer to it: an angel means God's protection,

a chakra-map means holistic health. Turrell's art, however, directly

presents the numinous for our attention. There is not a trace of any

particular religious or philosophical language in the works themselves.

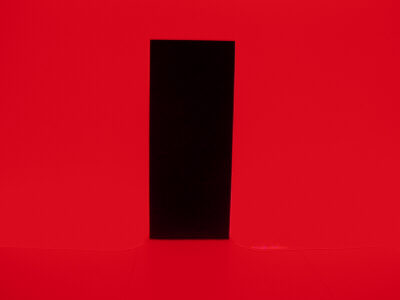

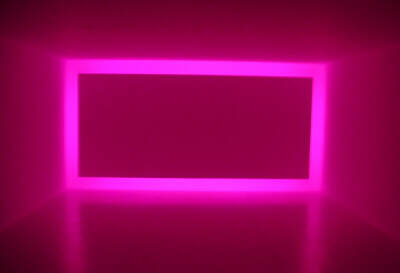

Consider Rise, a room with, at one end, a light source hidden

behind an opaque rectangular 'wall.' From around the edges of the wall,

light emanates, slowly changing in tone from red to purple to blue and back.

Turrell speaks of Rise and other works in the terms of Plato's Cave,

but he is not creating a diorama of the Cave so much as presenting

the object of insight itself for our consideration. As such, Turrell's

is a more direct - and thus more mystical - art than those which merely

quote the language of religion. Where such art, like religion, speaks of

Being, Turrell's, like mysticism, invites us to experience it directly.

Consider Rise, a room with, at one end, a light source hidden

behind an opaque rectangular 'wall.' From around the edges of the wall,

light emanates, slowly changing in tone from red to purple to blue and back.

Turrell speaks of Rise and other works in the terms of Plato's Cave,

but he is not creating a diorama of the Cave so much as presenting

the object of insight itself for our consideration. As such, Turrell's

is a more direct - and thus more mystical - art than those which merely

quote the language of religion. Where such art, like religion, speaks of

Being, Turrell's, like mysticism, invites us to experience it directly.

This is why viewing Rothko is a more religious experience than pondering a depiction of the Passion; art presents that reality of which the Passion narrative is meant to remind us.

Turrell's scientific theoretical language is in tension with the contemplative use of his art only if we suppose the numinous to yield only one vocabulary. In fact, avoiding religion-talk is the best way to talk about the object of religion. Really, the attention to perceptual-scientific detail cannot be in tension with this contemplative process: it is a refined manifestation of its truth. The Buddha is not vague; It is what is, in all the precise details. Likewise, Turrell's perceptual psychology is not the portal to some other 'spiritual' experience which then takes place in a fuzzy realm of emotional excitement; it is spiritual experience itself. This is how motorcycle maintenance is a Buddhist path, and "mountains are once again mountains" at the end of the Zen quest. Turrell invites us to sit down, stop the mind's ordinary processing of perception, and notice the "truth in light itself." If that isn't contemplation of God, what is?

Dick Cheney and the New Age

March, 2003

...and what to do about it

February, 2003

Anxiety on the national mall

January, 2003

Arte Povera, Damien Hirst, and postmodernism

December, 2002

Pierre Bonnard at the Phillips

November, 2002

Being at one with Being

July, 2002

What's the difference between laughing with art and laughing at it?

June, 2002

Zeek in Print

Buy your copy today

Germanophobia

Michael Shurkin

The Red-Green

Alliance

Dave Hyde

The Art of

Enlightenment

Jay Michaelson

yom kippur

Sara Seinberg

Josh Plays the Sitar

Josh Ring

Genuine Authentic

Gangsta Flava

dan friedman

saddies

David Stromberg

about zeek

archive

links