Sephardic Literature: The Real Hidden Legacy

Sephardic Literature: The Real Hidden Legacy

Reviewed:

The Schocken Book of Modern Sephardic Literature, Ilan Stavans, editor.

Schocken, 2005, $ 27.50

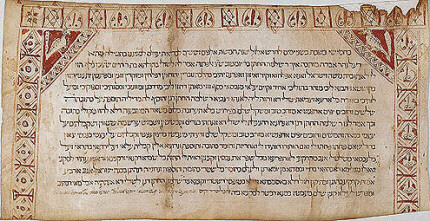

I am a Sephardic Jew with what most would consider a strong Jewish education--yet nothing I had learned growing up in Brooklyn or attending the Yeshivah of Flatbush gave me any reason to think that Sephardim had contributed at all to Jewish culture, especially modern Jewish culture. We were taught Buber and Soloveitchik in Jewish Philosophy, Wiesel, and Potok in our English classes, and the less said about our Jewish History program—where the teacher once told a cousin of mine that Sephardic history was not taught because “Sephardim have no history” —the better. We passed our high school years blissfully unaware of Hispano-Jewish poetry, Kabbalah, Maimonidean rationalism, the picaresque Arabian-style tales of Judah al-Harizi, the seminal grammatical studies of the Sephardi balshanim, and the poetical insights of Moses ibn Ezra. We had no notion of the historical works of Abraham ibn Daud, Solomon ibn Verga, and Joseph ha-Kohen, no hint of modern Sephardic Jewish writers, and certainly no clue that Sephardim, too, had experienced anti-Semitism, participated in Zionism, and suffered during the Holocaust.

The Argentine-born Syrian Rabbi José Faur, then a professor of rabbinics at the Jewish Theological Seminary, opened my eyes. In a lecture that shattered my world view he introduced me to two Sephardic writers I had never heard of, Edmond Jabès and the Nobel Prize winner, Elias Canetti. These two very different authors wrote from a perspective utterly different from any I had encountered before, a distinctly Sephardic point of view that was at once eminently modern and grounded in the cultural values and the epic history of the Jews of Muslim Spain and the East.

Faur inspired me to read: first the intitial volumes of Jabès’ Book of Questions, a massive seven-volume project that was composed of mystical aphorisms and digressive meditations on existence and the meaning of life, then Canetti’s Auto Da Fé, the epic novel, his Crowds and Power, and portions of his classic memoir. More crucially, I found a key to a whole new world of Jewish culture and literature in Susan Handelman’s The Slayers of Moses, who, among other things, introduced me to the work of another Sephardic Jew, Jacques Derrida, who stands at the very center of current intellectual concerns.

Faur’s approach was to relate the work of modern writers and philosophers to the classical rabbinic tradition, with a particular emphasis on the Sephardic heirs to the Mishnah and Talmud, men like Sadya Ga’on, Sherira Ga’on, David Nieto, Elijah Benamozegh, and many others. Faur also did something that was alien to Flatbush Modern Orthodoxy yet--I would learn--completely natural among Sephardic religious thinkers. He brought Judaism together with the humanities and the sciences, and he invited his students to walk freely through the thought and writing of Gentiles. The strict dichotomies common to Ashkenaz between right and wrong, Torah and maddah need no longer apply. Indeed, Faur’s work-in-progress, later published as Golden Doves with Silver Dots, was a freewheeling reconstruction of Jewish ideas that had few intellectual boundaries. His sources, though unknown to me, were all an organic part of my historical heritage as a Sephardi.

Another major discovery for me was Ammiel Alcalay, who had also been influenced by Handelman and Faur and who delved into Classical and Modern Sephardic literature and poetry with an inspiring vigor and engagement. Alcalay exposed me to Sephardic ideas and values and made me conscious of the elision and occlusion of Sephardic culture by Ashkenazim.

Another major discovery for me was Ammiel Alcalay, who had also been influenced by Handelman and Faur and who delved into Classical and Modern Sephardic literature and poetry with an inspiring vigor and engagement. Alcalay exposed me to Sephardic ideas and values and made me conscious of the elision and occlusion of Sephardic culture by Ashkenazim.

In 1983 Alcalay gave me a copy of a proposal he had been working on with the distinguished Sephardic poet and polymath Edouard Roditi, who was best known for his translation of Albert Memmi’s classic autobiographical novel Pillar of Salt. This project, which remains unpublished, was called SEPHARAD, a massive two-volume anthology of Sephardic writings. I had never heard of most of the writers he had listed, yet I felt that there was an energy and a momentum to this work of Sephardi intellectuals like Faur and Alcalay that I wanted to be a part of.

Both Alcalay and Faur explored the phenomenology of Eurocentrism and found malignant strains of racism in Ashkenazic Jewish culture. Alcalay was explicitly political in his use of the anti-Imperialist critique of Edward Said, while Faur wrote a scathing attack on the religious traditions of the medieval Franco-German Tosafist school that brought his reader to the same conclusion: Ashkenazim had misrepresented the classical Jewish tradition of the Bible and Talmud. Both writers ultimately came to the conclusion that European culture was a pox on the Sephardim and the medieval Arab civilization that nurtured it. Alcalay went so far as to relate the collapse of Sephardic history under Zionism to the depredations of modern Imperialism.

Sephardic Literature: The Real Hidden Legacy

David Shasha

plus Jordan Elgrably on the Sephardic Intellectual

Guilt and Groundedness

Jay Michaelson

David: The Original Drama King

Dan Friedman

The Doctor

Sarah Schulman

After sepia photographs

Hila Ratzabi

A War in Postcards

Alon K. Raab

Archive

Our 760 Back Pages

Zeek in Print

Summer 2005 issue now on sale

About Zeek

Mailing List

Contact Us

Subscribe

Tech Support

Links

Limited Time Offer

Two years of Zeek in

print for only $20.

Offer expires 9/30.

Click this button

to purchase:

From previous issues:

Meditation and Sensuality

Josh Goes to Services

Becoming Jewish-ish

Jay Michaelson

Josh Ring

Jeff Leavell