It is fitting that the Leibowitz’s moment in the mainstream comes during a period of potentially radical political realignment in Israel. Sharon’s redirection of Likud has rendered old distinctions of “right” and “left” hazy at best, and possibly obsolete. A common agenda—at least for the moment—has emerged under the rubric of the “Israeli center,” which, in reality, is a patchwork of moderate left and right wingers. In a variety of ways, Leibowitz’s political views match the idiosyncrasies of Israel’s new center.

On the one hand, Leibowitz was unambiguous in his contempt for the territorial ambitions of the right-wing. On the other, he rejected the leftist notion of “land for peace.” This odd position matches the thinking of Sharon’s coalition, which has rejected the approach of “land for peace”—hence withdrawal—but which also operates under the assumption that a credible peace agreement is not on the table now or at any point in the near future—hence the unilateral aspect.

The issue of the territories, Leibowitz wrote on the heels of Israel’s victory in 1967, had nothing to do with land and everything to do with the population that lives in the land. That year, when leaders of both the right and left hailed Israel’s new territorial gains, Leibowitz warned of the ruinous nature of occupation and of the looming threat of a demographic collapse.

In a 1968 essay, “The Territories,” Leibowitz wrote that sovereignty over the Arab populations of both the territories and Israel would “effect the liquidation of the state of Israel as the state of the Jewish people and bring about a catastrophe for the Jewish people as a whole; it will undermine the social structure that we have created in the state and cause the corruption of individuals, both Jew and Arab.” He predicated the disintegration of the Jewish labor force, the dangerous disillusionment of the Arab Israeli sector, the pervasive culture of corruption and the intifadas.

But Leibowitz, who was an Orthodox Jew, saved his harshest critique for the religious-based territorialist arguments. In that same essay from 1968, he wrote: “Counterfeit religion identifies national interests with the service of God and imputes to the state—which is only an instrument serving human needs—supreme value from a religious standpoint. The ‘halakhic’ reasons for remaining in control of the territories are ridiculous, since the state of Israel does not acknowledge the authority of the Torah and the majority of its inhabitants reject the imperative demands of the Mitzvoth.” In other words, religious nationalism is a paradox: while nationalism serves the material needs of the collective the Jewish religion, according to Leibowitz, places the collective in the service of God. (Leibowitz insisted that self-serving motives have no place in religion even, for example, the 'spiritual' desire to worship.) To Leibowitz, the territorial messianism of the Israeli religious right distorts the true nature of Jewish messianism; he associates authentic messianism entirely with pure religious actions—following the Mitzvot—not secular achievements in war and politics.

Characteristically, Leibowitz went even further, stating that the religious-nationalist veneration of the Land was a literal form of idolatry, a sanctification of nationalism that would have cataclysmic results. “Not every ‘return to Zion’ is a religiously significant achievement,” he wrote. “Another sort of return is described in the words of the prophet: ‘When you entered you defiled my land and made my heritage an abomination” (Jeremiah 2:7).” In other words, at the height of Israeli triumphalism, at precisely the moment when religious messianic fervor was at a fever pitch, Leibowitz was comparing it to abomination.

Leibowitz’s withering critique of the right and especially of the religious right would seem to place him in the camp of the left. Indeed he was often mistaken as a leftist. But he had plenty of criticism for the left as well. Throughout his life, Leibowitz remained deeply skeptical of the possibility of reconciliation between Israelis and Arabs. In an 1976 essay entitled “Occupation and Terror,” Leibowitz rejected the “land for peace” approach, calling it a “slogan that means holding on to the territories indefinitely.”

Why? Because "dialogue with the Palestinians is not likely to take place on the sole basis of the explicit intention to return the territories after reaching an agreement. Honest dialogue is not possible between rulers and ruled: it is possible only between equals.”

Leibowitz sided neither with right nor left. On the one hand, he concluded that “a program of ‘peace (or agreement) in return for territories’ does not seem feasible. Evacuation of the territories necessarily precedes any serious effort toward peace." (emphasis added) Yet on the other hand, he said, "this is stated without illusions: while evacuation of the territories is a necessary condition for peace (or an agreement under pressure of the superpowers), it is not certain that that it is also a sufficient condition….there is no guarantee that evacuation will bring us real peace, or even an agreement granting reasonable security.”

Although he never ruled out the possibility for reconciliation in the distant future—or under the pressure of the world powers—Leibowitz thought that peace was a very remote scenario. He believed that the concept of “land for peace” was flawed and untenable. Full and immediate withdrawal was an absolute necessity. Ideally, though wildly improbably, withdrawal might create the conditions necessary for a future peace. At the very least, though, it would allow Israel to retain the integrity of its democracy and spare Israeli society the ruinous ramifications of occupation.

According to Leibowitz, Israel’s security will come neither from the vision of wide borders—and is, in fact, weakened by the population that lives within these borders—nor will it come from half-baked “peace” schemes. He was, in effect, a leftist on territorial issues (with no patience for religious arguments) and a rightist on peace prospects. This bubbling brew of ideas is, in short, what characterizes the new Israeli center; it describes the fragile coalition that made the disengagement possible. And it’s likely that only someone as politically credible and shrewd as Sharon could have pulled it off. He was, after all, shrewd enough to appoint a Leibowitzian as his deputy.

The Jerusalem Same-Sex Attraction Group

Phil S. Stein

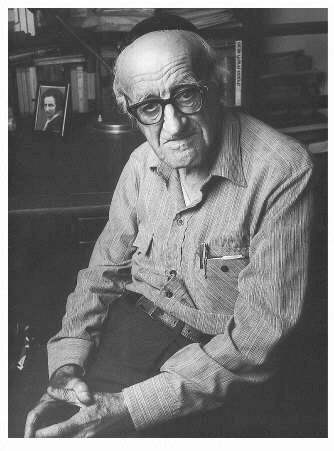

The Second Coming of Yeshayahu Leibowitz

Avi Steinberg

An Account of the Saltscape

Joshua Cohen

Fresh Baked Bread

Jay Michaelson

Out of the Depths

Lorna Knowles Blake

Lore

Adam Lavitt

Archive

Our 790 Back Pages

Zeek in Print

Fall 2005 issue out now!

About Zeek

Mailing List

Contact Us

Subscribe

Tech Support

Links

From previous issues:

Fleeing Edges

Hyatt Regency Dead Sea Resort

The Place of Anger

Noam Mor

Rowena Silver

Jay Michaelson