An Altar of Earth:

An Altar of Earth:Reflections on Jews,

Goddesses and the Zohar

1.

For many years, as I sat in synagogues, someone on the bimah would make an off-handed reference to the evils of idolatry. Many Jews who would never think of condemning the religious practices of Australian aborigines, Peruvian shamans or Buddhist nuns, and who might even enjoy the art in a Catholic church, give sermons about how worshipping images or praying to multiple deities is the root of all evil. Traditional teachers often equate idolatry-that is, worship of multiple gods, worship using images, or worship of components of the natural world-with murder, child sacrifice, and incest. Less traditional ones still condemn idolatry, but identify its evil with the worst kind of misguided materialist beliefs (worshipping one's money, for example). In Torah study sessions, I have seen individuals share their private ideas about God's tangibility or presence in nature, and even point out these ideas when they appear in a Biblical text. But then, someone asks "Isn't that pagan?" as if the conversation is now over. Paganism is bad. Even a hint of paganism is bad. That is the Jewish position.

What is so bad about paganism? For some Jews, it is a matter of ethics. Many have argued that paganism, because of its multiple gods, its focus on nature, and/or its multiple images of God, does not promote ethics or unity among humankind and therefore leads to atrocity. Yet both pagans and "monotheists" (a difficult distinction, as some pagans are monotheists) have massacred innocent people, conquered countries, enslaved the poor and members of other nationalities and races, etc. Some pagan societies are peaceful, and some are violent and warlike; we could say the same for Jewish, Muslim, and Christian societies. I value Jewish theological and ethical traditions, and believe that the Torah comprised a powerful critique of the religions of its time and region. Yet looking at history, it would be hard to make the argument that monotheism promotes universal brotherhood and sisterhood or that it is more ethical by definition than polytheism. Nevertheless, I hear these arguments all the time in shul.

Others say the problem with polytheism and paganism is not ethics but theology. Notably, I have heard this critique leveled many times in (and at) the Jewish feminist community. For the last fifteen years, I have been part of the community of Jewish feminists who are attempting to re-vision God: to re-experience God as not only male, but also female. At this point in time, some Jewish feminists prefer gender-neutral and/or impersonal language for God, but many revel in personal, anthropomorphic God-images that include the pregnant woman, the midwife, the seamstress, the bereaved mother bear, the Lady Wisdom who cries in the streets for people to discover the truth. All of these images have their sources in Jewish tradition, and all come from Jewish texts. Why, then, have they been repressed? God has many attributes, many names. What is the great danger if some of those images are female?

Part of the perceived danger is that using feminine language for God will lead to paganism. And why would that be a problem? Many fears have been expressed: Having both masculine and feminine languages for deity will lead to our creating two gods. Using feminine language will make us think of God as earth-mother; we will think that God forgives all things and our sense of good and evil will disappear (Paula Reimer expressed this in the nineties in an article in Conservative Judaism). We will begin to invoke the fertility goddesses of Canaan, which our ancestors rejected as evil (Cynthia Ozick). We will alienate ourselves from the human-Divine drama of monotheism (Tikvah Frymer-Kensky) or from Jewish communal norms (Judith Plaskow). All of these fears stem from a sense that if we come face to face with a goddess-figure, She will be exactly what the patriarchal, Talmudic critique of Her says She is: an untruth about God.

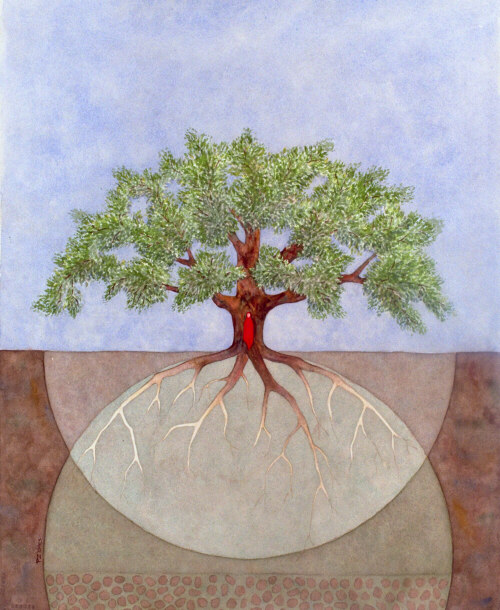

As a result, many Jewish feminists seem to believe that we should suppress any desire to read stories of goddesses as in any way sacred or connected to the Divine. Yet suppressing a desire never completely works in practice. While some Jewish feminist (and, of course, non-feminist) theologians may be able to legislate against goddess images in their intellectual structures, Jewish mystics and poets, modern and medieval, often perceive the Divine feminine outside the conventions and fears of the Jewish community. They may see the Goddess-and/or God-not only in text but in the trees and the sun and the moon, just as pagans do. They may see her as "dark womb of all," 1 as if She gave birth to the universe (a pagan image Genesis emphatically edited out). Many of us 2 find divinity not only in Jewish texts and prayers about the divine feminine, but in myths of goddesses as well.

1 Zohar III, 65b

2 See the writings of Lynn Gottlieb, Susannah Heschel, Leah Novick, and Kim Chernin, among others.

Jews, Goddesses

and the Zohar

Jill Hammer

Hasidism and Homoeroticism

Jay Michaelson

Lag B'Omer:

Sound & Image

Andy Alpern and

Shir Yaakov Feinstein-Feit

Couple

Ari Belenkiy

One Ring Zero

Paul Fischer

Josh's Jury Duty

Josh Ring

Archive

Our 480 Back Pages

Saddies

David Stromberg

Zeek in Print

Spring/Summer 2004 issue now on sale!

About Zeek

Mailing List

Contact Us

Subscribe

Tech Support

Links

From previous issues:

Radical Evil

Michael Shurkin

Constriction

Jay Michaelson

Two Rituals

Joshua Bolton