The romantic individualist is the ideal subject for the Hollywood story, but the climax of Cool Hand Luke is his romantic failure. When Luke falls, the lens of the mechanical camera is identified with the lenses of Mr. Mirrors; they (and we) share the satisfaction - if one can call it that - which comes with Luke's climactic failure. The film seems to revel in his rebellion but actually seems to revel more in his defeat. Like Mr. Mirrors, we see, but are not seen; we may take a stance of cold detachment, or Brechtian complex seeing, but even if we sympathize, our feelings are concealed from the hero. The system wins, Cool Hand Luke seems to say, and we are all part of it.

An ironic footnote, thirty five years later, is how the lives Newman and Schwartzenegger have played out the opposing roles of Luke and Mr. Mirrors/Terminator: Newman is selling salad dressing to subvert the system while Schwarzenegger has translated his success at the Hollywood system into politics and is now Governor of California.

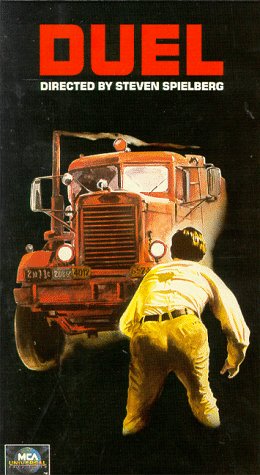

Losing the Duel

Losing the Duel

Steven Spielberg, in a rare Kafkaesque mood after the end of the sixties, dwells on Dennis Weaver's road rage in his 1971 Duel. In that film, the story of a suburban businessman travelling across the California desert to a sales meeting is pre-empted by his primal driving duel with a truck that seemingly wants to drive him off the road. The businessman's insensitive treatment of his wife, his banal concerns about his job, and the inane banter of the radio soon pale into insignificance next to this attack on his life, which he combats with increasingly attenuated rationalizations until his paranoid instincts fully take over. He ends up winning the duel (he jumps from his car just before it, and the truck chasing it, fly off a cliff) but losing his humanity: as his car and the truck plunge down the cliff he prances ape-like over the death of his enemy.

The truck has glass windows but we never see through them. Like that of the prison guard, the identity of the driver remains a mystery to us, and a source of intense irritation to Weaver. Ignoring the basic assumptions of the rules of the road - perhaps the primary code of the late twentieth century - seems an affront to civilization. The illusion of the spirit of the law as symbolized by the highway code is shown to be contingent on a near parity of power: in fact, only the letter of the rules apply if you have enough horsepower. And a minor road incident becomes a duel to the death if that power is threatened.

Although Weaver physically wins the duel, he has lost all semblance of civilization and, in triumph, only proves that the spirit of the system is contingent upon power and the only triumph is to acquiesce. If Newman's Luke is the martyr who loses the battle but saves his soul, Weaver's businessman is the antihero who prevails in battle at the cost of his soul. In both cases, that which is blocked from vision, obscured by opaque glass, is mechanical; it is the evil that is beyond good and evil, the mechanistic system which denies good and evil entirely. This system is impossible to see the camera cannot penetrate it and resists any attempt at humanization. It is precisely this system which stands in contrast to that which is seen through glass: humanity.

The Spiritual Foundations of Bushism

Jay Michaelson

Sex and the Golem

Joshua Axelrad

How Jewish is Modigliani?

Esther Nussbaum

Steel and Glass

Dan Friedman

No Matter What, I Wish You Luck

Chanel Dubofsky

Falafel Ghosts

Shaun Hanson

Archive

Our 500 Back Pages

Saddies

David Stromberg

Zeek in Print

Spring/Summer 2004 issue now on sale!

About Zeek

Mailing List

Contact Us

Subscribe

Tech Support

Links

From previous issues:

Schneiderman

Eliezer Sobel

Dead Sea

Debra Bruno

The Virtue of Mediocrity

Michael Shurkin