Steel and Glass

Like cleaning a mirror to remove a blemish that actually exists in the subject being reflected, critiquing a system in which one partakes is a losing proposition. This is true for all mass media which seek to critique "the System" in one form or another, but it has been especially true for films because, historically, they have had to rely on substantial amounts of capital for their production, capital that has come from large corporations or governments with a vested interest in maintaining the status quo. Yet this has not stopped filmmakers from trying to provide such a critique and, this month, I want to talk about three instances of their use of glass to do so.

Glass is a necessary part of the cinematic process. Film is a particular way of seeing and, rather than the vitreous humour through which human artists perceive the world, the camera - cinema's seeing eye -- looks through a glass lens. Not only does film see through a glass eye, but it also projects its vision through another glass lens out onto the screen. Like those ancient pictures where a beam projecting out of the eyes of the figures purported to show the mechanism of perception, the contemporary screen shows how the cameras eye colours (and is coloured by) our view of our world.

Cool, Manly, and Threat-free

Cool, Manly, and Threat-free

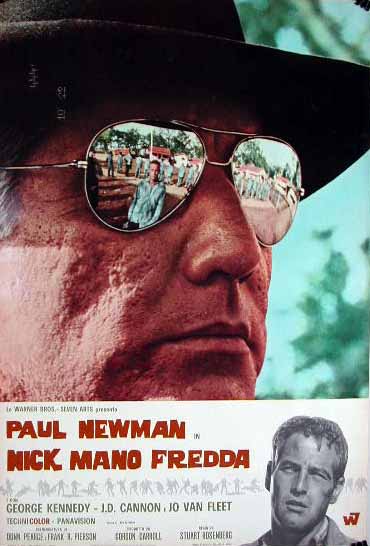

In Cool Hand Luke (1967), Paul Newman plays the eponymous hero who, despite his individual charisma and bravery, is beaten down by a series of systems. The film begins with a drunken Luke decapitating parking meters and being arrested. We find out, on his arrival at the penitentiary, that as a soldier he had been awarded medals for bravery, but he ended the war as he had begun it, as a private. After the military and civilian life, the regimented communal life of the prison is the site of his final rebellion. His series of daring escapes and stands against authority rattles everyone except one guard, who wears mirrored sunglasses.

Luke's colleagues are by turns excited and despairing of Luke's lack of self-concern; the prison dog-handler is beside himself because Luke runs one of the dogs to his death; even the warden ends up losing his cool in the face of Luke's noble obstinacy. However, as an exemplar of the system, both in his imperturbability and in his absolute anonymity (hidden behind one-way glass), the guard in the mirror sunglasses remains calm. Because Mr. Mirrors sees the world with the equanimity of the well-oiled cog, he can outcool Luke.

The cliche that eyes are the windows to the soul seems borne out by the impenetrability of the 'soulless' prison guard. Because we never see Mr. Mirrors' eyes, we begin to suspect that he, like the gun he so expeditiously and ostentatiously uses, is a machine with no soul. This trope is a common one. The spookiness of the Borg in Star Trek comes not from their kinky leather outfits but from the prosthetic eye that is a facial symbol of their connection to the hive mind - the system. In the Terminator series, the costume designers likewise take the cliché of police sunglasses, signifying blind, anonymous enforcement of the system, and exaggerate how they shield the unseeing glass eyes so that the machine-like system is incarnate in its enforcers.

The Spiritual Foundations of Bushism

Jay Michaelson

Sex and the Golem

Joshua Axelrad

How Jewish is Modigliani?

Esther Nussbaum

Steel and Glass

Dan Friedman

No Matter What, I Wish You Luck

Chanel Dubofsky

Falafel Ghosts

Shaun Hanson

Archive

Our 500 Back Pages

Saddies

David Stromberg

Zeek in Print

Spring/Summer 2004 issue now on sale!

About Zeek

Mailing List

Contact Us

Subscribe

Tech Support

Links

From previous issues:

Eye Candy

Michael Shurkin

Everybody wants to play with a bigger train set

Dan Friedman