How Jewish is Modigliani?

How Jewish is Modigliani?

Reviewed:

Modigliani: Behind the Myth

at the Jewish Museum

Launching its centennial celebration with a blockbuster exhibition of the works of Amedeo Modigliani, the early-20th century Italian-Jewish painter, is particularly fortuitous for the Jewish Museum of New York. It allows the museum to stake a claim as a serious art museum while examining the question of the artist's problematic Jewish identity, as well as the social and historical context of his paintings, drawings, and sculpture. The museum's association with the Jewish Theological Seminary also brings to mind one of JTS' founders, Sabato Morais, a revered rabbi who was a product of the same city of Leghorn (Livorno), Italy, that gave us Modigliani.

Subtitled "Beyond the Myth," the Modigliani exhibition attempts to correct previous theories and attitudes toward the artist and his work. As Modigliani's daughter, Jeanne, complained in her 1958 biography, the artist had come to represent for most the archetypical Bohemian, a handsome Italian leading a debauched life that included womanizing and abuse of alcohol and drugs. The aim of the exhibit is to move away from this image both by taking a closer look at his work and by locating it within the context of his Italian-Jewish background.

The show is installed under rather arbitrary nomenclature: "Caryatids", "Sculpture", "Return to Painting", "Portraiture", "Montparnasse" and "Nudes". In each section the viewer is confronted with a rich array of the artist's work, brought together from public and private collections from around the world. In the gallery where the caryatids are displayed, one can contemplate the figures which take their name from columns in architecture that depict a feminine form supporting a weight, either of another decorative element or the roof. These provocative figures, recalling the forms of classical antiquity are drawn by Modigliani with sculptural intensity. They link the artist to his Italian heritage; not only had he visited art museums and ancient sites in Rome and Florence, he had experimented in sculpture while still in his teens, before leaving for Paris.

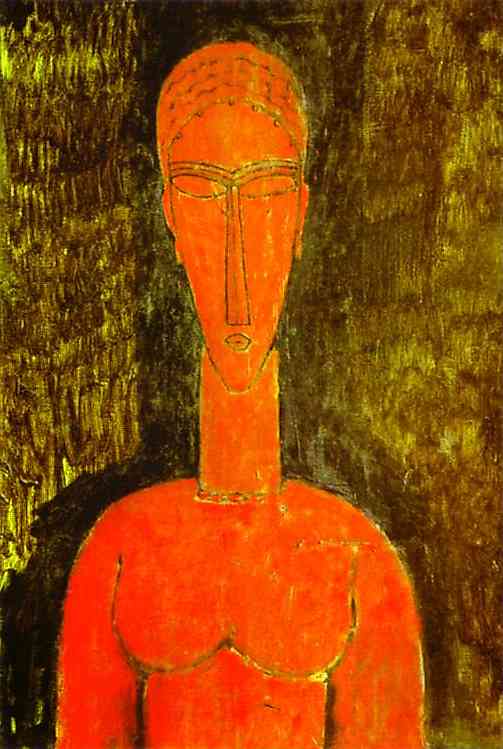

Modigliani's interest in the human form is evident in the carved heads in the "Sculpture" section, some executed in classical style, others in a more modern idiom. Modigliani had met Constantin Brancusi in 1909 and his affinity to sculpture was renewed. The sculptures dating from 1910-1913 are juxtaposed with two paintings entitled Red Bust and Large Red Bust, deliberately underscoring their illusion of dimensionality. Scarcity of stone material combined with Modigliani's own failing health brought about what the curators call the "Return to Painting." Included in this section are a variety of drawings, some of which depict subjects or symbols that lead to a consideration of the personal identity of the artist. It is the only section that contains works that hint at Modigliani's philosophical concerns, and one of the few places we find Jewish culture. Old Man at Prayer, Woman, Heads and Jewish Symbols, Motherhood, studies executed in pen and watercolor and others done in pencil or crayon are described by the curators as illustrative of his family's rich Sephardic heritage and socialist political involvement.

Modigliani's interest in the human form is evident in the carved heads in the "Sculpture" section, some executed in classical style, others in a more modern idiom. Modigliani had met Constantin Brancusi in 1909 and his affinity to sculpture was renewed. The sculptures dating from 1910-1913 are juxtaposed with two paintings entitled Red Bust and Large Red Bust, deliberately underscoring their illusion of dimensionality. Scarcity of stone material combined with Modigliani's own failing health brought about what the curators call the "Return to Painting." Included in this section are a variety of drawings, some of which depict subjects or symbols that lead to a consideration of the personal identity of the artist. It is the only section that contains works that hint at Modigliani's philosophical concerns, and one of the few places we find Jewish culture. Old Man at Prayer, Woman, Heads and Jewish Symbols, Motherhood, studies executed in pen and watercolor and others done in pencil or crayon are described by the curators as illustrative of his family's rich Sephardic heritage and socialist political involvement.

The Spiritual Foundations of Bushism

Jay Michaelson

Sex and the Golem

Joshua Axelrad

How Jewish is Modigliani?

Esther Nussbaum

Steel and Glass

Dan Friedman

No Matter What, I Wish You Luck

Chanel Dubofsky

Falafel Ghosts

Shaun Hanson

Archive

Our 500 Back Pages

Saddies

David Stromberg

Zeek in Print

Spring/Summer 2004 issue now on sale!

About Zeek

Mailing List

Contact Us

Subscribe

Tech Support

Links

From previous issues:

The Ritual of Family Photography

Amy Datsko

Couple

Ari Belenkiy

The Aesthetics of Power

Michael Shurkin