It's a 500-mile pilgrimage from my family's home in Maryland to Tiffin, Ohio, where my grandmother, aunts, uncles and cousins live. Though many of my childhood memories are rooted in this small town in the Midwest, my family only visits there two or three times a year due to the large distance and my parents' objections to airplanes. Babies are born, great-aunts die, divorces are finalized, cousins graduate from high school and I don't see my family until months after the fact. There is an underlying fear in families separated by states (or even oceans) that we don't really know each other, that our only connection is in our chromosomes. We see each other a few times a year and rush to catch up on the other three hundred and fifty five days. When my grandfather was alive, we would congregate at my grandparents' house for the holidays and we would always have a photo taken of the cousins (the third-generation) on their couch. In a family that is separated by distance, photographs become an important mode of communication. Just as we want self-portraits to show our healthy, graceful progression through the years, we want family portraits to display the maturation and development of a shared family history. Families pose for portraits to show themselves, and later remind themselves, of how they looked at a moment in time. There is a specific style of dress, an arrangement of bodies, a set of facial expressions that govern how the image is constructed. There is an ideal of how we should appear in family photos; we want to have similar physical features to prove our relation, we touch each other to show our closeness and care, we appear happy and comfortable around each other. Photographs are used to mark time, to show others how we are superficially doing; they give us proof of our existence.

It's a 500-mile pilgrimage from my family's home in Maryland to Tiffin, Ohio, where my grandmother, aunts, uncles and cousins live. Though many of my childhood memories are rooted in this small town in the Midwest, my family only visits there two or three times a year due to the large distance and my parents' objections to airplanes. Babies are born, great-aunts die, divorces are finalized, cousins graduate from high school and I don't see my family until months after the fact. There is an underlying fear in families separated by states (or even oceans) that we don't really know each other, that our only connection is in our chromosomes. We see each other a few times a year and rush to catch up on the other three hundred and fifty five days. When my grandfather was alive, we would congregate at my grandparents' house for the holidays and we would always have a photo taken of the cousins (the third-generation) on their couch. In a family that is separated by distance, photographs become an important mode of communication. Just as we want self-portraits to show our healthy, graceful progression through the years, we want family portraits to display the maturation and development of a shared family history. Families pose for portraits to show themselves, and later remind themselves, of how they looked at a moment in time. There is a specific style of dress, an arrangement of bodies, a set of facial expressions that govern how the image is constructed. There is an ideal of how we should appear in family photos; we want to have similar physical features to prove our relation, we touch each other to show our closeness and care, we appear happy and comfortable around each other. Photographs are used to mark time, to show others how we are superficially doing; they give us proof of our existence.

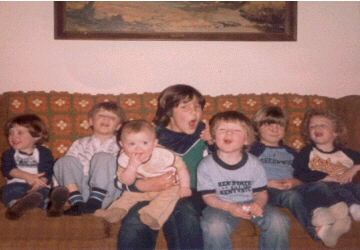

For fifteen years, my cousins and I performed a family photographic ritual, imbued with symbolism. We sat on our grandparents' couch; though we could have easily moved to a more beautiful place, the couch implied consistency. We were always convened by my Aunt Barb; as the oldest-and essentially, matriarch-of the second-generation, she guaranteed that no one would forget. The photographs themselves became a representation of my family's stability and the comfort I found in it, a sense of progression, but still a core of consistency. Each family received a copy of the photo taken each year, an image usually displayed on a refrigerator, which served as a reminder of who we are and how we fit into a history.

In the first photo I have (c. 1984), there are seven of us on the couch. The symbolic costume in this picture: t-shirts, many advertising Kent State University, where several of our parents went to college. The shirts have several layers of meaning. First, our parents' own histories. Second, the fact that during these years, our parents mainly determined our "costumes;" later, we would develop our own styles, and the photos reveal our growing independence. And third, the theme of dressing-down; there are no fancy dresses or coats and ties. Our costumes represent ease, a tendency towards the casual, in the ritual, reflecting the comfortable, relaxed relationships valued in my family.

Zeek in Print

Spring 03 issue available here

Shtupping in the Shadow

of the Bomb

Marissa Pareles

The Mall Balloon-Man Moment of the Spirit

Dan Friedman

Beats, Rhymes & Nigguns

Matthue Roth & Juez

Fish Rain

Susan H. Case

Anti-fada Paratrooper

Michael Kuratin

Josh Gets his Checkup

Josh Ring

Plague Cookies

Mica Scalin

The Ritual of Family Photography

Amy Datsko

about zeek

archive

links