Jews on Stage

Jews on Stage

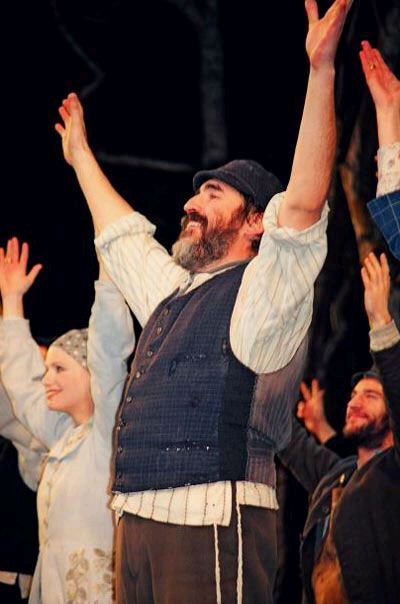

What’s up with all the Jews on stage in New York? Yes it’s true that New York is more Jewish than London or Chicago, but this past year has seen a remarkable number of explicitly Jewish plays in New York: Fiddler on the Roof at the Minskoff Theater on Broadway, Billy Crystal’s 700 Sundays at the Broadhurst Theatre, and Jason Biggs and Molly Ringwald in Modern Orthodox at the new Dodger Stages are the most obvious. Off-Broadway too has been offering a smorgasbord of heimishe drama: Jewtopia has prospered at the Westside Theatre, A Novel Romance by the Folksbiene Theater played at the JCC in Manhattan, and Gareth Armstrong’s Shylock is still downtown at the Perry Street Theatre. Even Spamalot – the new Monty Python musical – remarks unashamedly that you need a Jew to come to Broadway and, to make the point, makes this the theme of the stand-out new musical number. While the Pythons are deliberately overstating the case, it seems as though giving a Jewish theme to your drama in 2005 is like chicken soup in the joke about a fatally ill man – it might not help, but “it cudden hoit.” Why is this? And why now?

I. Is it good for the Jews?

In the Jewish Quarter of Prague stands a small building earmarked by the Nazis to be the “Museum of the Lost Race.” During the war Nazis confiscated Jewish artefacts from all over Europe and carefully shipped them to Prague to store them for the museum. Jews were too important to Nazi ideology to risk losing through physically annihilation. The hated “Other,” in the form of Jewish history and Jewish characteristics (as portrayed, of course, by the conquering Nazis), had to be commemorated in order to be properly hated, even after the Jews had been turned into a ‘lost’ race. It would have been the final injustice – a constant and ongoing defamation of Jewish identity by those guilty of our slaughter.

Sixty years on from the final Allied destruction of the Nazi infrastructure we still worry about the justice of public representation. (Imagine if Schindler's List had been directed by a Christian: What are they going to make of us now?) The mini-furore that surrounded the opening of the ‘ judenrein’ production of Fiddler on the Roof at the Minskoff Theatre in February was surely a shadow of the same fear. The excitement, fuelled by rumours of an entirely non-Jewish cast, came to focus on the fact that the lead was going to be played by Alfred Molina, a non-Jewish Englishman of Spanish descent who was, even worse, about to become Doc Ock – the next baddie in the Spiderman franchise. How terrible for the Jews this seemed. Now that Harvey Fierstein has taken over the lead, the fuss seems like ancient history, but why the trouble to begin with? The words and the story are unimpeachable – the film is as good an introduction to Jewish history as any college course -- why should we worry that the cast was non-Jewish?

When I was at college there was a production of Fiddler on the Roof which included a Sri Lankan friend of mine in the chorus of Anatevka. His presence as an apparent non-Jew with a complexion not often seen in turn of the century Eastern Europe was, at the time, an amusing incongruity, but just as funny was the fact that he was both by far the shortest in the chorus and had a beard pasted on to his otherwise baby smooth face. More subtly, in the same production the part of Chava was played by an actress with pale skin, blonde hair, and blue eyes. Although I know Jews who have similar features, it happened that she was not Jewish. The tension of her appearance and her character – Chava marries out of her father’s faith – made for a complicated feeling of inevitability that owed much to her colouring (she was more ‘Aryan’ than the Cossack whom she married) but little to her faith. In each case they brought more, and different, emotional as well as physical, abilities to bear on the parts they played.

So shouldn’t we be happy that the wider world is interested, even excited, not only to act in, but even stage a Jewish play? And wouldn’t it likewise be great if a Jewish organization put on A Raisin in the Sun? Like Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, such a cross-cultural embrace would not be a colonial or racist appropriation of another culture; it would be meant as a compliment to the excellence of that particular play and the African American experience in general. But suppose the Jewish organization went one step further and highlighted the racist context in which the play had been written by putting on the play in blackface. Perhaps that's the better analogy, given the kitsch, nostalgic portrayal of the Jewish community in any production of Fiddler. Tevye is so extreme, he's like a Jewish Sambo.

There are two crucial distinctions, however. The first is that, although Jews remain a vulnerable minority, in the United States, at least, we are not a disadvantaged one. While there are Jews living in poverty, and those who suffer discrimination, we also have our fair share of moguls and politicians – we are not, as a community – systemically subjugated in the same way African Americans are today. In the same way that Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra clearly has plenty to say about East – West relations but a staging of the play on Broadway is not going to reinforce Roman (Italian) prejudice against Egypt (Africa), the pogroms from which Tevye’s family flee at the end of Fiddler are distant enough from the contemporary American social context not to reinforce the prejudices that are portrayed.

The second distinction is linked to what is, for me, the crucial and particular aspect of Jewish identity. Unlike the odious prejudices of racial identification which tend to be somewhat narrow in their classifications, Jewish identity is polymorphously perverse. Perverse because the radically manifold nature of Jewish identity means that we have been open to (and guilty of) racial, religious, nationalist, and geographic prejudice depending upon the particular community, the historical situation, and even, to some extent, the individual Jew. This protean shifting between the categories of what Wittgenstein might call “family resemblance” allows us, as Jews, to distance ourselves legitimately from any single category of identification.

Neurotic Visionaries & Paranoid Jews

April 7, 2005

Jews on Stage

Dan Friedman

Out of Bounds

Angela Himsel

Masoretic Orgasm

Hayyim Obadyah

Messianic Troublemakers: Jewish Anarchism

Jesse Cohn

The Hasidim

Hila Ratzabi

Discipline

Jay Michaelson

Archive

Our 640 Back Pages

Zeek in Print

Spring 2005 issue now on sale!

About Zeek

Mailing List

Contact Us

Subscribe

Tech Support

Links

From previous issues:

James Lee Byars and the Number Ten

Abi Cohen

Retrato de Familia

Bara Sapir

Drawing a Line in the Cheese

Michael Shurkin